J.D. Hutchison has died.

For those of you not familiar with the Appalachian music scene, particularly as manifested in southeastern Ohio, a small introduction to that culture is probably appropriate.

One Saturday the first summer I lived here, I was sitting on the swing on the back porch of my house, which is located on a low ridge. To the west I heard some variety of rock music being played in the valley below. From the east there were banjo, fiddle, and some other less distinct instruments, being played by a group of people in that valley. The two were in the same key, so it wasn’t jarring. Instead, it was typical.

The old music and newly written music reminiscent of the old style are as much a part of the fabric of this place as are the hills themselves, or the bits of coal you’ll find in the creek bed when the water is low. You’re always hearing that someone plays and you’re never very surprised.

It wasn’t, for instance, until a few days after his death this year that I learned my friend Ernie Midkiff (whose centenary would have been a week from tomorrow had he lived) was once a well known fiddle and mandolin player hereabouts. Not long after moving here I got to know Pete Hart a little. He’d worked for the phone company for a long time, but his fame came from playing mandolin in the highly regarded Hart Brothers bluegrass band.

I used to spend my time restoring old banjos, especially the incomparable products of The Vega Company, particularly their Tu-ba-phone and Whyte Laydie. This passion was made possible by the presence locally of Stewart-MacDonald, the world’s premier seller of parts, tools, and supplies for those who make or fix stringed musical instruments. It is primarily a mail-order company, but people there got accustomed to my showing up to buy stuff, for cash, right there. (Though my receipt would come in the mail a few days later, along with yet another copy of their tempting catalog.) If I were lucky, the Stew-Mac guy I’d deal with on a given day was a tall, thin fellow always wearing a Greek fisherman’s cap. If I needed a calfskin banjo head, he’d let me back into the warehouse to go through the stack of them to pick out just the right one. (Someday I must write about the glories of mounting, drying, and using a skin banjo head.) Anyway, it was only after a year or so of this that I learned that the young guy in the hat was Mike McGovern of the then-famous McGovern Brothers BlueGrass Band. When I completed my pride-and-joy banjo, I did not think it done until Mike McGovern had seen and approved it.

Living not far from the Stew-Mac warehouse was and is Dan Erlewine, widely regarded as the world’s best fixer of guitars and related instruments. He’s also a better’n middlin’ guitar player.

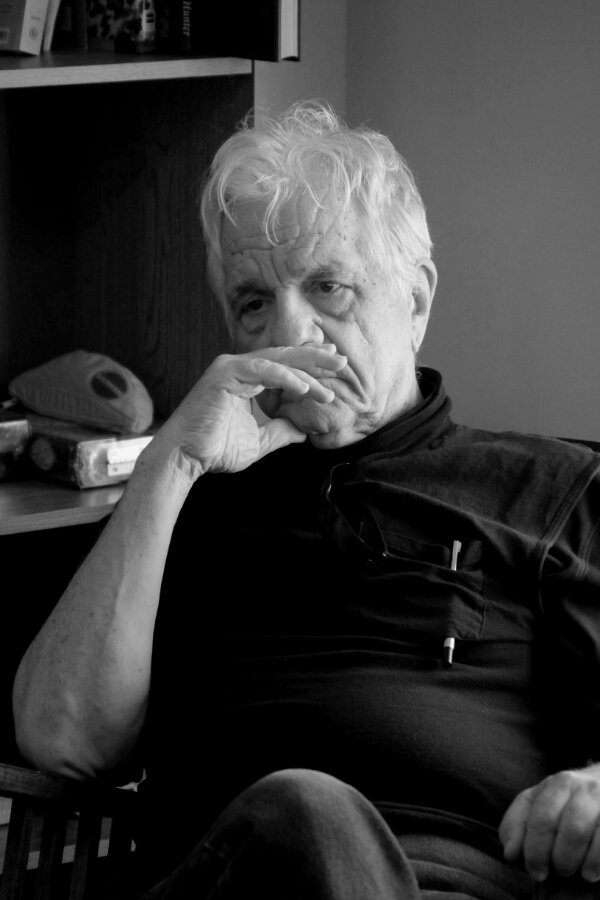

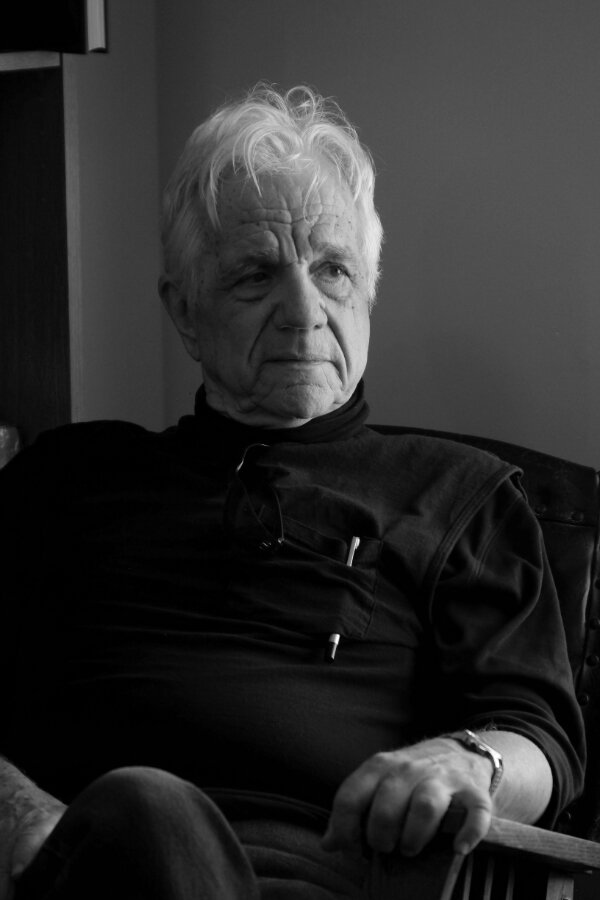

This is a musical place, and towering above them all in a lot of musical ways was big, gruff, friendly John. D. Hutchison. Actually, “J.D.” — few knew what the initials stood for, and when referring to him the last name was usually superfluous, too. I don’t remember how I got to know him, but somehow I did. It probably began at the legendary Blue Eagle Music, where musical folk spent more time than we should have, in the before time. I remember one day stopping by and the proprietor, Frank McDermott, brought out a beautiful antique banjo made of some blond wood. “That would look really great with ebony buttons from Stew-Mac,” I said. “Funny you say that,” replied Frank. “J.D. said the same thing the other night.” I felt that in some small way I had arrived: Having independently hit upon the same aesthetic judgment as J.D. Hutchison in a matter involving a musical instrument, even something as seemingly trivial as banjo tuner knobs, was a thing to smile about.

At some point my editor at The Athens News, Terry Smith, excitedly told me he had arranged an interview with J.D. and I could come along and make pictures. He was surprised when J.D. greeted me as warmly as he would have an old friend and began talking about some old banjos he’d seen. The resulting article dealt with an exciting new album J.D. and Realbilly Jive were putting together, with Tim O’Brien producing. That day or the next I got to drive down an impossibly steep and curvy driveway to the recording studio where the band was making the album. I made some pictures there, too, but my favorite time was photographing J.D. and Mimi Hart, herself a local legend (and of no relation to Pete Hart) recording some vocals. They were having a good time, which is or ought to be an important part of making music.

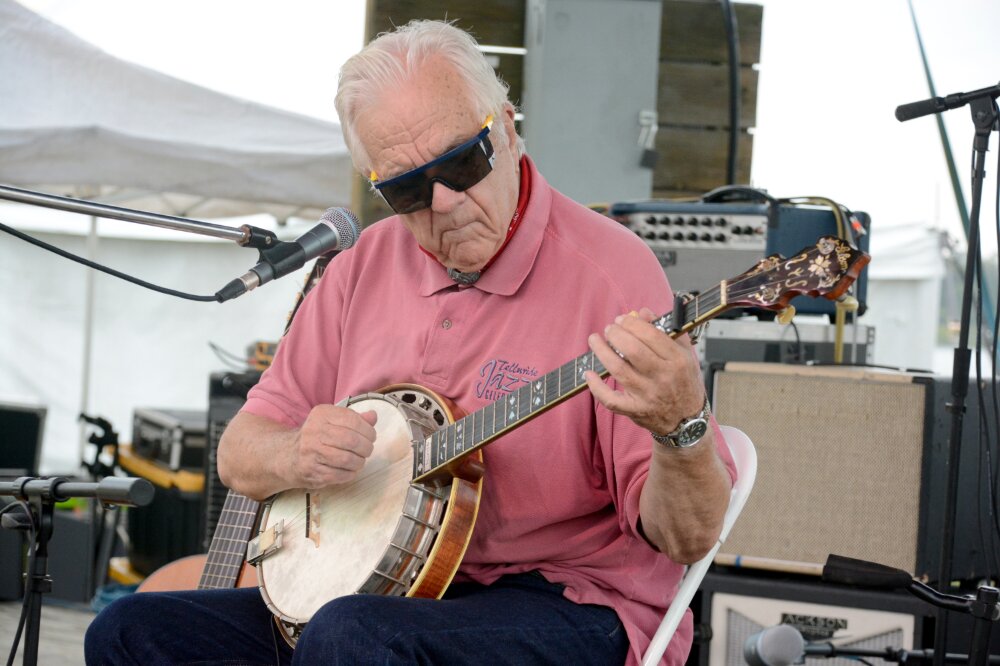

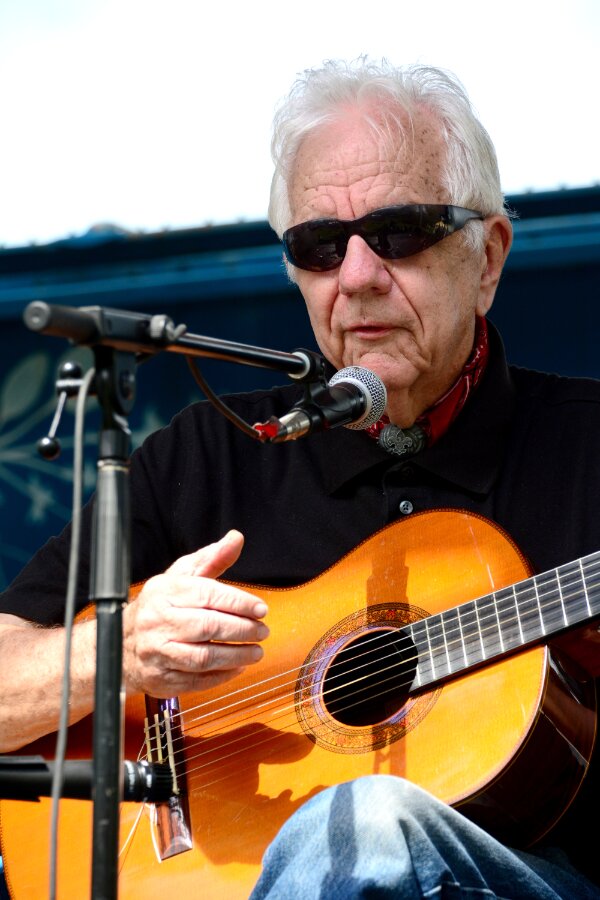

There are a lot of live music venues around here, and a lot of festivals that are about or feature music, and J.D. would play them all, wearing his signature (usually red) bandanna and wowing the audience. I may have misled you into thinking that J.D. was primarily a banjo player, but his chief instrument, among the many he played, was the guitar. That having been said, the performance of his that I remember most fondly was a banjo piece, a proper clawhammer rendition of “Marching Through Georgia,” that he did while sitting on a folding chair on the edge of the stage at the Pawpaw Festival in 2016.

He played at the Nelsonville Music festival for many years; I remember a few years ago when he was all gruff and grumble — and rightly so — for having been scheduled for the Boxcar Stage on a very hot day just at the time when the sun would blast down and hit him in the face. He played his usual superb set, then retired to the shade to watch the other performers and to engage with badinage among his friends there.

It is impossible to put music into words, but this is the internet, so I don’t have to try. I’ll link to some things that will give you a sense of what a musician and human being he was and will make you smile, too.

For instance, here’s an interview and some playing from the Nelsonville Music Festival in 2014. And here he is at The Union in 2014, a few months before it burned down in the Union Street fire of November 2014. (It got rebuilt.) Here he is, a capella, also at The Union.

Here’s a short musical biography of the great man. While the video’s caption says he “has managed to stay one step ahead of fame for his entire life,” it also demonstrates that he was well known and highly respected by some musical names you most likely know.

You’d run into J.D. here and there. He was a denizen of junk shops and thrift stores, which for some reason didn’t seem unusual. I remember one bright morning when Jorma Kaukonen (of The Jefferson Airplane, Hot Tuna, and a sparkling solo career) and I happened upon J.D., Frank McDermott, I think John Borchard, and others at the Casa, the local semi-countercultural restaurant, where they were having breakfast and we were about to. (The paper needed an aerial picture of the Ohio University stadium, and Jorma loved to fly his drone, and he was going to be in town to get his truck serviced, and, well, a plan came together. Which fortunately included breakfast at Casa.) As an outsider, I was able to stand back just enough to take in the sheer amount of musical talent and accomplishment present in that small space, and to wonder how it would all have come together in a dinky little town in the Appalachian foothills. It was a moment.

Nobody has seen much of anybody these last two years. It is at our peril if we assume that once the curtain is lifted everything will be as it was. We might have taken time off, but time itself didn’t. It was on Jorma’s blog last week that I saw sad and alarming words: “My friend J.D. Hutchison, a more that fine musical artist and writer of songs, looks like he might be pulling into that final walk.” I do not know the details, but apparently J.D.’s final illness came fairly suddenly. Then, Tuesday, word from Mimi Hart: “Our beloved brother has passed. We’ll never see his likes again, nor shall we ever forget him.” Wrote Jorma, “I met John thirty years ago in the Blue Eagle Music Co. on Court Street in Athens, Ohio. Ethan Greene and J.D. were hanging out by the old pot belly stove and holding court. J.D. was a musical giant and a one of a kind human being. He was also a friend.”

I’ve been all over the place with this column, rambled a bit about this event and that one. I suspect J.D. would have understood and I hope that you do, too.

As I think about it more and more, J.D.’s death comes as shock not because he wasn’t old, because he was old. The shock is tinged with regret that no first-class documentary maker ever made a movie about his life and music, but that’s scarcely unique.

I think it’s because J.D. Hutchison wasn’t the sort of person who would

die. If you stopped to consider, he seemed more the kind of man who

would just stop moving and gradually turn to stone, there forever.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation