Time is a funny thing.

Well, no, time is time. Our perception of it is where things go haywire. We’re not very well equipped to comprehend the passage of time or its implications.

I have old friends whom I vaguely remember as having spoken to fairly recently, but when I stop and actually think about it I discover that “fairly recently” is actually some time in the 1990s.

This figures in the sad anniversary we’ll observe Saturday. It is easy to recognize that two decades have passed since the awful and confusing morning of September 11, 2001, but it is harder to reconcile that 12 of the 13 Americans murdered by an Islamist bomber in Kabul week before last were infants on that lamented late summer day (the 13th was 10 years old when 9/11 was committed).

To them the terrorist attack on our country was as remote as December 7, 1941 is to most of the rest of us. It happened, it was atrocious, and it was all wrapped up before we entered the scene at all.

This is the week when everyone who has something to say, and many who do not, will write about that miserable day 20 years ago. We’ll hear even more about it from persons, may God forgive them, who see it as a “marketing opportunity.”

It had been my plan to put something in this space to explain to all these young people why the cowardly attack we’re remembering is important to them (in case the deaths of a dozen of them week before last is insufficient). I thought it might be in the form of a letter. But the excellent Lionel Shriver, an American expat living in England, did it far better than I would have. Her letter is to someone who was in the World Trade Center that morning.

So I’ll recount that day from my own peculiar perspective, which might or might not provide a tiny illumination, and perhaps meditate on how little we’ve learned.

While the World Trade Center’s design had its critics, I loved the thing, the place. It was completed in the spring of 1973, so its arrival in New York didn’t precede mine by much. By coincidence, my favorite nonfiction book has long been 1974’s The Curve of Binding Energy, by John McPhee, which in the author’s methodical and fascinating way explains atomic bombs through asking the question: Could terrorists readily make a bomb that would bring down the World Trade Center?

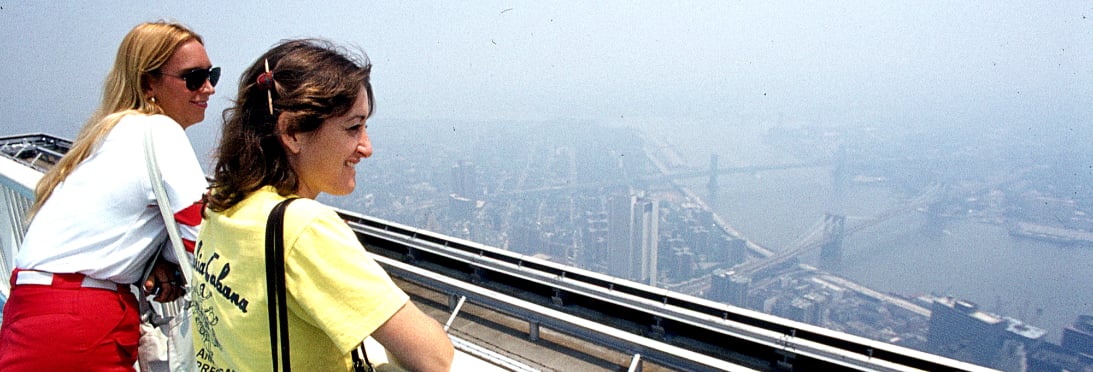

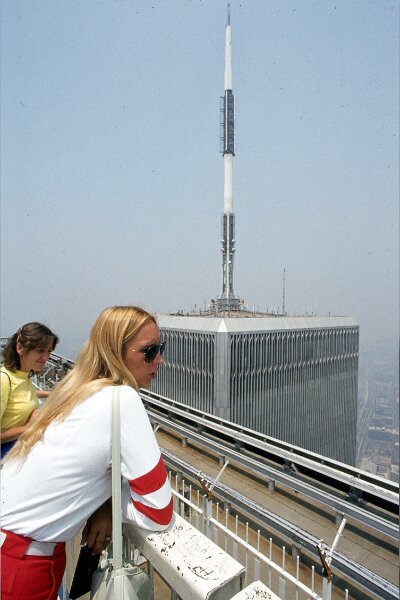

As a reporter in New York I visited the place frequently. New York Telephone, later NYNEX, was fond of holding news conferences there, complete with elaborate spreads from Windows on the World, the posh top-floor restaurant. The Port Authorioty of New York and New Jersey had its offices there. A news guy soon got familiar with the World Trade Center. When the younger of my two sisters and a friend visited from Florida, the World Trade Center was one of the places I took them. We stood on the roof of the South Tower and were annoyed that the day was hazy, reducing the distance we could see.

They were amazed by the place, as well they should have been. No one who was never there can grasp the sheer size of the towers. Each of the two had a square footprint 210 feet to a side. They were 110 stories tall. The foundation itself extended seven stories into the ground, below the water table so a huge concrete casting called “the bathtub” had to be built. Each floor of each building had an acre of leasable space; each tower took up 60,196,500 cubic feet of space and together they were only a little smaller than NASA’s giant Vehicle Assembly Building at Cape Canaveral. About 50,000 people worked there each day.

They were often the subject of breaking news, as the morning of August 7, 1974, when high — really high — wire artist Philippe Petit walked a cable he and assistants had stretched from the top of one tower to the top of the other, 138 feet across and 1365 feet high. A little more than two and one-half years later, the country awakened to the image of George Willig — “the human fly” to the tabloid newspapers and television news programs — climbing up the outside of the South Tower. It was then the third-tallest building in the world; Sears Tower in Chicago was almost 70 feet taller and the North Tower of the World Trade Center was eight feet taller than the southern one. Willig made it to the top and, like Petit, was arrested. The city ultimately fined hit $1.10, a penny for each floor.

On February 26, 1993, a little after noon, lower Manhattan was shaken when an Islamic terrorist bomb went off in the parking garage beneath the North Tower. Six people were killed, more than a thousand injured. There are famous pictures of employees of North Tower businesses leaving the area, their faces streaked with soot.

Then came what shall ever be known by the shorthand, “9/11.”

I’d been up late the night of September 10, 2001, so it was my wife’s phone call from her law office — “An airplane has crashed into the World Trade Center” — that awakened me. I figured that it was some sort of general aviation aircraft that had gone wrong. That kind of thing happens from time to time. In 1945, a B-25 bomber crashed into the Empire State Building, in the fog. (September 11, 2001, was as clear and crisp a late summer morning as you could imagine.)

From our little horse farm in Newtown, Connecticut (famous, before and after, for other things), I turned on the television, for no particular reason to CNBC. Commentator Mark Haines was talking with people speculating about the plane crash as a long-lens camera framed the World Trade Center (which no one regularly called the “Twin Towers”). Just then, the second plane hit. It was no general aviation airplane. My initial thought was that something had gone horribly wrong with the aviation navigational aids along the heavily traveled Hudson River corridor, but that thought quickly passed.

I phoned my wife, from whose office windows the World Trade Center could be seen across the western end of Long Island Sound. My sister is a hospital physician, and I composed a quick email note and sent it to her pager: “two airplanes, both big jets, have crashed into the world trade center in an apparent terrorist attack.” It is timestamped 9:12 a.m., 10 minutes after the second plane hit. She would later tell me that her hospital, in Milwaukee, went onto the kind of alert that prepares for many incoming victims, in case New York and other nearby hospitals were overwhelmed.

They weren’t. Television broadcast scenes of New York hospital emergency room people waiting for the hundreds of injured. But there weren’t many injured people. Most everybody got killed.

I dashed off a quick email note to Rush Limbaugh at his super-secret address: “So, my friend, what do we do now?” I’d later learn that he was not broadcasting that day and had been in transit, and when he read my note he was not sure at first what I was talking about.

And this wasn’t even the end of the beginning. Reports came in that an airliner had crashed into the Pentagon. There were continuing updates about another plane that it was said had been hijacked. Someone reported a bombing at the State Department. The accounts, some true, many not, were broadcast, padded with speculation and conjecture — Would the Air Force shoot down a passenger plane headed for a populated area? Where was the President? Were we at war? If so, with whom? Had Saddam Hussein been behind it? Al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden?

It is impossible to characterize the roiling confusion, anger, terror, and shock of that day. One of the benefits of modern technology is that we do not have to describe it. It has all been preserved at archive.org. If you are so young that you don’t remember that day or remember it indistinctly, I strongly advise you to spend many hours there, because it is crucial to your understanding the world we live in, even today. It is important to pick a channel and watch it in real time for several hours. The highlights you can find anywhere kind of miss the point. If you remember it well, I still think that it is a good thing to revisit from time to time. What you’ll find there is as shocking as and in some ways more important than the events of Friday, November 22, 1963 and the days that followed.

Going from channel to channel in New York that stunning morning, it was easy to get overwhelmed; in fact, it was just about impossible not to get overwhelmed. Even the Home Shopping Network replaced its programming with a card to the effect that this was no time to buy stuff, and viewers should be watching the news instead. (Strange how it is little things like that which even now bring a lump to the throat. Among them is a story published a short time later in, of all places, The Onion.)

The buildings collapsed. We barely had time to consider what New York City would be like with just one World Trade Center tower when the second one came down.

The horses still needed to be fed, so about noon I stepped outside. It was a beautiful day in every respect. I was taken by the silence, until I remembered that all aviation in the U.S. had now been grounded. Our farm was under a significant air traffic intersection and the absence now of the distant sound of jet engines was noticeable. I don’t think I’d experienced this much quiet in many years. The horses, as always, gazed out with their combination of boredom and curiosity. They had no idea of the horror erupting not many miles away.

Back in the “real world” of the television the confusion and terror continued. Mayor Rudy Giuliani (the primary election over his replacement had been that day, but got postponed) appeared, next to his advisers, all of them covered in plaster dust and ashes. They were in some room lit as if it had been prepared for a hostage video. The president, it was erroneously reported, had gone into hiding. There was no way to separate the true from the speculative. Normally the sane among us apply a bit of common sense, but the things we knew had happened were so beyond the realm of comprehension that there was no longer any guide, any compass.

I phoned my wife again and urged her to come home. Nothing good was going to happen that day at a law firm. She agreed. I figured that she would want to follow the events on television, but no — she headed to the barn where her show horse was kept and went riding. I went along. I didn’t want her to be alone in a suddenly more dangerous world. We had no idea what really was going on.

As the day progressed the news continued to be awful. An announcement around 5 p.m. that a 47-story building, 7 World Trade Center, was about to collapse went almost without notice. A 47-story skyscraper! The confusion continued in part because broadcasters largely failed to correct erroneous reports sent out earlier in the day. Some of this would linger for years; it could be that some of it still does.

That night there were pro-Islamic demonstrations in Central Park, as well as the usual “prayer service” kumbaya crowd with its candles and feel-good humanist gibberish.

The next evening, September 12, a belligerent Joe Biden, of modest intellect but not yet senile, appeared on Larry King’s show and demanded retribution. He was excited about how helpful NATO would be. (This is the same NATO he would stab in the back this year, when he surrendered in the war he had championed on Larry King’s show that night.) The Senate vote to go to war, he predicted, would be 100 to 0. It was approved in the Senate on September 14, 98-0, and in the House of Representatives the same day 420-1, the lone negative vote being that of California (of course) Democrat (of course) Barbara Lee.

(Ironically, it was Biden who as vice president 10 years later would argue against the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, sponsor of the September 11 attacks. To the benefit of everyone except bin Laden, President Obama gave Biden’s opinion the weight it deserved and ignored it.)

We attended a town gathering in the stadium at Newtown High School. Local coverage in the New York suburbs centered on the commuter train stations and the cars there that had gone unclaimed because their owners were now presumably dead, and the station in nearby Bethel had some of those. The gathering took the tack that we should try to understand why the terrorists did what they did. At the time I thought that it was just about what one would expect. Since then I’ve come to think that the whole thing was barking mad. The two are not mutually exclusive.

Over the weeks and months that followed, things changed in large and small ways. Once the airspace was reopened it became more difficult to fly. There were stories of people being detained because they had fingernail clippers on their persons. We became generally more suspicious of each other; the distinguishing attributes characteristic of the 9/11 terrorists were not mentioned out of fear that someone would be offended. Juan Williams was fired by National Public Radio for saying that traditionally garbed Muslims on airliners with him made him nervous. Really.

The individual stories filtered down. Among them was that of a classmate of my wife. Working at the Cantor Fitzgerald investment firm, this young woman was on her way to work high in the North Tower, several floors above the spot where the first plane had already hit when she arrived. Helping people to safety, she was last seen headed back into the building to aid others shortly before it collapsed. Her infant daughter would never come to know her. Every Canter Fitzgerald employee who went to work that day, all 658 of them, died in the attack. More than 3000 children lost a parent that day.

People re-evaluated their lives and situations. We attended two weddings in the couple of weeks after the attacks. One, in western Massachusetts, had been organized by the couple soon after the terrorists struck. It was a time to re-examine the things that had been put off and postpone them no longer.

The other wedding, in Virginia, had been planned for some time. Driving there, I took the long way around Baltimore solely because it seemed to me that the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel was a convenient target of terrorists. Judging by the traffic I wasn’t the only one who took this into consideration. Driving back to Connecticut on the New Jersey Turnpike, I caught myself looking for a landmark, the first sign that home was within reach: the distant outline of the World Trade Center. On this trip the familiar and comforting sight was replaced by smoke that rose high in the air before heading out to sea.

(After a decade of all-heat, no-light argument, the distinctive World Trade Center was replaced by an unremarkable splinter building that’s of little use in identifying the New York City skyline — you now have to look uptown, to the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and Citicorp Center for that.)

A friend’s birthday party was organized in lower Manhattan November 16. The rubble that had once been the tallest buildings in the world was still smoldering, giving the air a bad taste. There were bits of ash and partially burned paper on the streets and sidewalks even then, stuff that had once been someone’s very important office work.

Time plays tricks on us. We easily forget that at the time of the attacks on America the internet’s graphical user interface — the WorldWide Web — was less than 10 years old. An early if not the earliest internet “meme” (though the usage hadn’t been invented yet) was a phonied up picture of a fellow known as “tourist guy” standing atop the World Trade Center, a commercial airliner headed straight for him. It gained wide currency when it was spread on the web as supposedly having been discovered when film from a camera found in the rubble was developed. In fact, it was a picture made by Hungarian tourist Péter Guzli in 1997; he modified it in Microsoft Paint, of all things (even though it helped give rise to the verb “photoshop”), and sent to friends as a joke. They apparently passed it around.

On October 7, President George W. Bush announced the first attack on terrorist enclaves in Afghanistan. That Hindu Kush country, geographically long on history but culturally isolated in many ways, had just undergone a civil war, with the apparent victors being a cult of Islamic fundamentalists called the Taliban. The group was known in the West mainly for its destruction of Buddhist statues, some of them thousands of years old. They were nuts, was the general opinion, and it was a shame about the artifacts, but we had things more important to worry about than a bunch of medieval tribalists throwing rocks at each other and shooting each other with the rusty relics of a recent, failed Soviet invasion.

Though we wanted nothing to do with Afghanistan, people there wanted something to do with us. In the caves and hideouts along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, members of the Taliban and its retail subsidiary, Al Qaeda, plotted to do harm to the West, America in particular. It was there that the September 11 attacks were plotted, along with other terrorist atrocities. The president had decided to clean the place out. Which in due course we did. It took longer than expected, but by 2014 or so the situation was largely under control. American troops began to come home. A small force to assist the growing Afghanistan national military was all that would be needed.

Gardeners are familiar with a plant called the bindweed. With years of hard work it can be brought under control to some extent, but only a little bit of inattention will undo all that work and the gardener has effectively to start again from scratch. So it is with jihadi terror organizations. Once knocked down, they can be fairly easily kept from becoming too much of a problem. Ah, but look away for even a little while. . .

It was of course Donald Trump who decided in his typical what’s-in-it-for-me fashion that there were political points to be scored in the demonization of and withdrawal from what he called “endless wars.” The Taliban, who had been picking at the edges of Afghanistan all along, couldn’t have agreed more. (It should be remembered that Afghanistan hadn’t been anything anyone would call a war for close to a decade.) Trump’s lickspittles cut a deal with the Taliban that wasn’t worth the four pages it was written on, but it would get the president past the election, the actual goal.

Trump lost, so he wouldn’t have the opportunity to fling down and dance upon the sham agreement as soon as he had found someone else to blame for it. His successor, Joe Biden, is a master at identifying the worst possible path and following it. He embraced the deal that until then no one had much liked and few had taken seriously.

It would have been very difficult to imagine on that morning 20 years ago that our response to the abominations of September 11, 2001 would ultimately be to surrender unilaterally to those who committed the atrocities, leave them thousands of hostages as leverage against us, and equip their army with our best and most modern fighting gear, all while the president mumbled something about our having over-the-rainbow military skillz. While he patted himself on the back in recent weeks for having solved an intractable problem, his only real accomplishment was making the foreign-policy reputation of Jimmy Carter look good by comparison, a thing once thought impossible.

The U.S. military has 39,000 soldiers deployed in Japan, and 35,000 in Germany. We’ve had troops in some number in those places for 75 years. We have 24,000 in South Korea, where our military has been a strong presence for 70 years. Is the White House checking to see if it’s too late to surrender in World War II and the Korean conflict, thereby ending those “endless wars,” too? I write it as a joke, but with this administration (and the last one) today’s absurdity is tomorrow’s policy.

Only time will tell. You know, the way it put the lie to all that “never

forget” talk.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation