Many years ago a radio network colleague came into the newsroom one Friday night all excited. She and her well-known musician husband, confirmed city dwellers, were going to rent a car the next day and explore the countryside.

On Monday, I asked how the excursion had been. Her always cheerful expression turned into a horrified scowl.

“We turned around and came right back. The rats up there are three feet long!” They had seen one crossing the road at night.

After the laughter died down, a couple of us explained to her the difference between possums (or their Irish cousins, opossums) and rats.

Whenever I think of that incident, I’m reminded of a British television show of a bygone day. It was called “Connections” and was hosted by an amiable, professorial gent named James Burke. It sought to show how one event, discovery, mistake, or action resulted in another, which had its own offshoots, so this thing is the result of some other unrelated thing. A phenomenon the great political philosopher James Burnham had earlier summed up by saying, “It’s impossible to do just one thing.”

And all of this comes to mind more frequently than one would expect.

My favorite example is the story of the “kappa,” which I thought about over the weekend after I saw a program about the great Edo-period Japanese leader who came to be called Yozan. Born Uesugi Harunori, he gained control of the Yonezawa domain in 1767, when he was just 16 years old.

Yonezawa suffered frequent disasters and other hardships and was poverty stricken. By instituting serious reforms, he led his domain to a period of prosperity, and he is admired to this day. His story is worth learning, and you can find it here, for free.

Among Yozan’s reforms was agriculture. Cultivation of rice was essential, and as you’ll see if you watch the show, though he was the ruler even he cultivated a patch of rice, going out and working in it each day. Such a thing was unheard of at the time. (His rice field is preserved and producing, even now.) The people of Yonezawa paid their taxes in rice, as was standard in Japan. The tax was high, and every official along the way took a bite, literally.

Not specific to Yozan, and not entirely relieved by him, this system was rife with corruption and was generally levied more on how much the land could produce than how much it did produce. In times of droughts, pestilence, or bad harvests, rice growers faced the problem of feeding their own families, in that the tax levy generally didn’t decrease.

Nor was there any recourse, not that any tendency to object was found in Japanese peasant culture. Famous in Japan then and now is the story of Kiuchi Sogo, the headman of a village of 389 farmers near present-say Narita Airport near Tokyo (then called Edo, as any crossword puzzle addict can tell you). The village was in the Sakura domain and in the mid-17th century was ruled by Hotta Masanobu, who raised the taxes so much that many farmers fled, leaving their families behind. Though approaching shogun Tokugawa Ietsuna, the ruler of Japan, was forbidden by law, Kiuchi went to Edo, carrying a petition from the farmers begging for relief. Outraged, the shogun ordered the taxes lowered — but Kiuchi and his wife were crucified and their small children beheaded for his having dared to go to the shogun, someone far above his station. It is said that Kiuchi haunted Hotta and brought him great misfortune. Finally a shrine dedicated to Kiuchi was built and the hauntings ended. The shrine, near the airport, still exists today. There is a famous kabuki play about Kiuchi.

(And I got goosebumps when I found out, entirely by accident, that Kiuchi and his family had been executed on September 2, the same date I was researching him. He and his family died on September 2, 1653, though I have seen the date reported as having been in August or later in September. The shrine was built 99 years later. It is popular to this day, and last night in Japan — night before last here — worshipers held their annual all-night vigil in Sogo’s honor.)

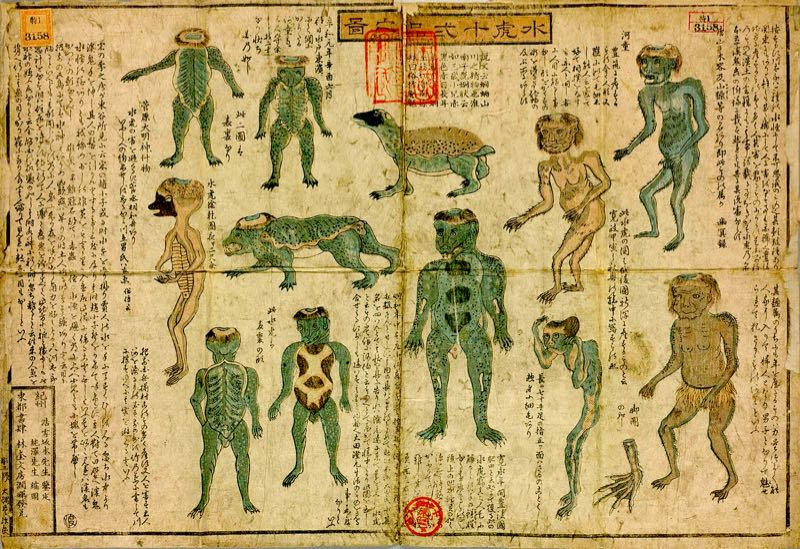

The story illustrates the culture of near-absolute obedience in Edo Japan. That culture led to what may have been the tragic tale of a particular Japanese supernatural being, the “kappa,” from the many such beings collectively known as “yokai.”

As the story has been handed down, kappa make their homes in rivers and streams, though they can leave the water. They have a turtle’s shell. Their heads have a dish-like dent at the top, and the story is that when kappa leave the stream this dent must be kept full of water or they become paralyzed. Kappa are said to drag people down to their watery deaths, after which the kappa eat them. But they also love cucumbers, it is said, and they are polite: if one approaches and its intended victim bows, the kappa will return the bow and spill the water from his dish-like indentation, so the victim can escape. It is noted that to this day there are old signs near bodies of water warning people to watch out for kappa. But kappa are sometimes characterized as being playful. And even now, people will sometimes write the names of their children and their birthdates on paper and throw it into the river. This sign of respect is said to protect the children from kappa attack. (Hey, we write letters to Santa Claus, okay?)

It is a peculiar bit of cultural heritage, don’t you think? Most folk tales, here and elsewhere, are to illustrate a point. There is a moral to the story. Admittedly, stories sometimes get embellished with successive retellings. Some yokai tales do have a moral. For instance, the “oni” specialize in punishing children who misbehave. But kappa seem to have no such purpose.

Japan is described as a polytheistic country. I’d make bold to take it a step further and call it omnithiestic. Everything has a spirit in traditional Japanese culture, and just as we all strive, or should, to get along with each other, getting along with other spirits is seen as the good and proper thing to do. (And no, I’m not being a heretic: the First Commandment does not say there are no other Gods but instead that no God must take precedence before the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.) So there is, for instance, a shrine at the foot of most mountains where one passing through pays respect to the god of that mountain, perhaps before climbing it. The prayer before one eats, which the Japanese honor far more consistently than most of us Westerners do, offers thanks for the life of whatever is about to be eaten (as well as those who played any part in its preparation, including perhaps the truck driver who brought the ingredients to the store). At the top of a long flight of steep stairs in Tokyo’s Shiba district is Atago Shrine, devoted to the god of fire protection — which makes perfect sense to anyone aware of the city’s history.

Which isn’t to say that all these spiritual beings are thought to be entirely understood.

Yokai have existed in Japanese culture for many hundreds of years, but kappa became widely known relatively recently, beginning in the Edo Period with the rice tax (called “kokudaka”), another datum important to our story. Some yokai explain things. Some do things. Some are merely observed, and kappa are of this last group.

There is a body of thought that seeks to explain the modern kappa as sometimes being a result of the rice tax, of all things.

I have heard it explained that when there was a bad crop or a particularly corrupt tax collector (which as we learned from the story of poor Kiuchi was something that took place), some families were able to survive only by reducing the number of mouths to feed, which is to say by killing one or more of their children. Historically, this was not considered wrong and was not an unusual response to hardship going back more than a thousand years in Japan. (And before you get all high and mighty, remember that in the U.S. alone more than 65,000,000 unborn babies were killed, as matters of convenience, from 1973 to 2020.) Life then was cheap. Obedience and face mattered (values not entirely absent from modern Japan).

The child would be smashed on the head, the body thrown in the river. Floating things with bashed-in skulls, bloated into a rounded turtle shape, would have been easily misidentified as they floated downriver, perhaps circling in eddies here and there.

There are a dozen species of turtles found in Japan. While many of them are of the Geoemyda family, primarily found in Asia, they also include the pet-shop favorite “red-eared” turtle found everywhere, and the common snapping turtle, the last of which is known both for dragging small ducks below the surface for food and for eating carrion. They are big and muscular. Their much larger relative, the alligator snapping turtle, is found in Japan, too. I personally have known a specimen weighing 218 pounds, its head as big as yours. They have powerful jaws, bad tempers, and are not to be toyed with. Not closely related and smaller, but as pugnacious, is the “big-headed” turtle. These are all mostly aquatic, coming ashore only to lay eggs or sometimes to sun themselves.

There are also numerous smallish turtles there. They are largely insectivores or plant eaters or both and are generally terrestrial. They love fruits and vegetables, of which cucumbers are a favorite. They are cute and pleasant, analogous to our own box turtles and wood turtles.

See where we’re going here? Kappa, by the way, means “river child.”

American reptilian legends generally revolve around snakes, and they are mostly wrong. A plumber I knew here in Appalachia once explained to me that I had to carefully watch my tomato patch lest “garden snakes” (garter snakes, also sometimes misidentified as “gardener snakes”) would eat the tomatoes. Which isn’t true — snakes are all carnivorous. The garter snakes came to eat the tomato worms that would eat tomatoes. He said nothing about box turtles, who eat tomato worms and tomatoes. We don’t generally ascribe supernatural properties to turtles, though we do it all the time with snakes (as do the Japanese).

Anyway, the path from a poor dead child, its head stove in, floating in a river, to dangerous turtles, of which there are some and they might well nibble on someone who had drowned, is obvious, albeit wrong. The inoffensive, cute, little terrestrial turtles that looked a lot like the dangerous ones and that like cucumbers, well, they’re obviously just a smaller version of the bad ones. Also wrong.

But we’re talking a long period of time when subsistence living was the order of the day, and those who had time to study the natural world much at all were happily in their palatial homes in the cities. There, in their silk robes, they might collect folk tales and try to make sense of them, but they had no reason to doubt them. (While thinking nothing of the value of non-noble lives.)

There are illustrations of kappa going back to the 800s, but it was in Edo Japan that the popularity — not just fear — of yokai took off. Since then, kappa have been among the most popular yokai. They are even favorite characters in anime, and appear in advertisements in Japan.

I have no idea if my explanation of kappa applies to all of them. I’d guess not. But I feel fairly confident that is explains some, perhaps many, of them. Thus we have a path — a connection — between onerous taxes in feudal Japan and the folk stories of strange, sometimes dangerous water spirits.

I hope you enjoyed the excursion.

Which you might have, unless you’re still in New York, afraid of the giant rats of Westchester County, where there are indeed giant rats, but they walk on their hind legs. But that’s a story for another day.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation