Do all families have a deep corporate interest in genealogy? I hope so, because it is fascinating and satisfying.

The subject swoops in unannounced and occupies my days every few years. Though I’m by no means an expert, I think I’m a relatively skilled dilettante and have a long, strangely constructed family tree to prove it.

I had no real interest in resuming my search for forebears just now, but circumstances had other ideas, as circumstances often do. If I’d paid attention I might have noticed that the genealogical phantom has been lurking nearby recently. There have been online discussions of remarkable ancestors with a distinguished historian and others (it is my good fortune to have a touch of Zelig in my constitution it seems).

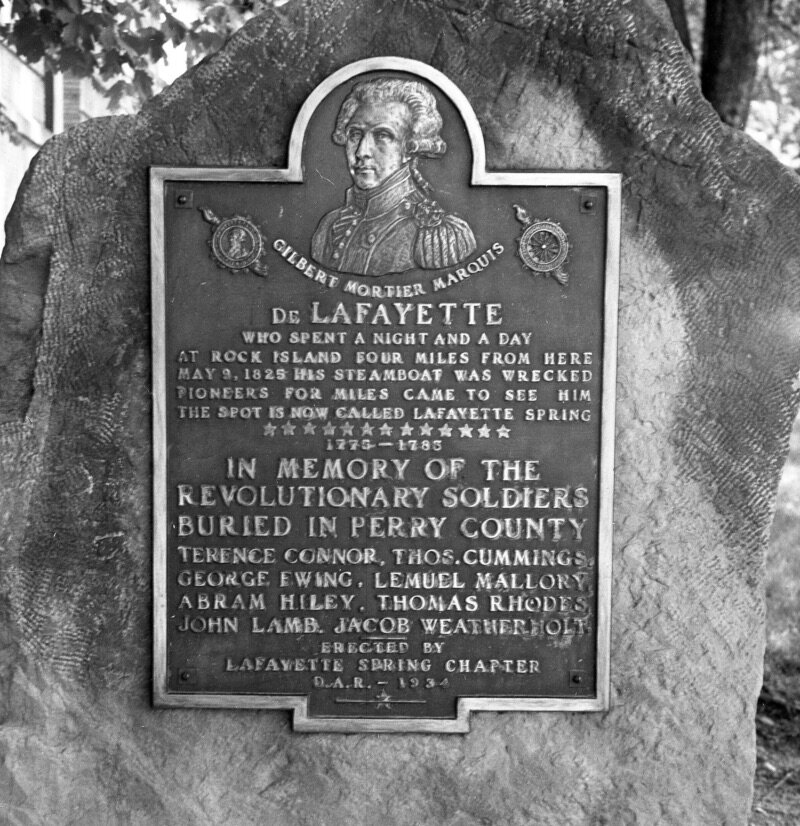

While recently scanning in old family negatives I found pictures that were taken on our annual trips to southern Indiana, a place literally dripping with history: There are some made at Lafayette Spring, near the spot where Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, Marquis de La Fayette, French hero of the American Revolution, was shipwrecked in 1825. A marker there listed Perry County, Indiana, soldiers in the Revolution, among them Thomas Cummings, our ancestor.

I sent that picture, which is reproduced here, to my sisters, with a note to my older younger sister that it might be the proof she needed in her interest in joining the Daughters of the American Revolution.

A few days ago aforementioned older younger sister sent me a note asking how she could assemble the evidence necessary to join that organization. This actually made sense: she is a physician. I am a reporter. I’m better at tracking down the non-physiological.

In my occasional dips into genealogy I’ve discovered several ancestors who fought in the Revolution, a couple who fought in the War of 1812, at least one who was an officer in the Civil War (also known to some as the War of Northern Aggression, but my great grandfather was a Union captain, so I don’t call it that). I knew that the family tree bore belligerent fruit. We have lots of ancestors who fought in the Revolution (a requirement for membership, as the name suggests).

Genealogical sources are difficult, and the farther back you go the harder they get to find. In my family’s case, we’ve known all along about two of the four lines whence my grandparents sprang: My father’s mother’s family we have in America back to the 1600s, likewise my mother’s father. We have a relative who was hanged as a witch in Salem, Massachusetts, and another who was kidnapped and held for years by Indians in New England.

For the longest time we weren’t sure about my father’s father’s side of things, tracing them only to Pennsylvania in 1821. It turned out that this was due to a misspelling that led us to look near Pittsburgh, but no: My umpteen-great grandfather, John Powell, showed up near Philadelphia around 1699. He founded Powell’s Valley, Pennsylvania. (I’ve not found him on the passenger lists between Europe and America at and before that time, which is disappointing but not surprising: people arrested in England for various offenses were often sentenced to be “transported,” which is to say banished to far-flung parts of the empire. People who sailed with one name frequently disembarked in their new land having assumed a different one. I haven’t given up hope, but am not confident that I’ll ever know about the Powell line before John’s arrival. Nor were names of particular importance before and even during the 18th century.)

My mother’s mother’s family arrived here in the mid-1800s, from Germany. We have her lineage going back through the 15th century, though the reason we do is terrible. In the late 1930s, a relative still in Germany sent my grandmother’s family a letter and a copy of the family genealogy going back that far. It had been assembled to prove that they had no Jewish ancestors. “We do not know how all this will turn out,” the letter said. Not a judgment, just a statement of fact, or at least so I hope. They were strange: if they had a child die, the next child of the same sex who came along was given the dead child’s name. Nominal recycling.

The reason I mention all this is that there was not always a bureau of vital statistics. People’s names and their significant dates were not always recorded. If they had been, genealogy would be easy.

Once you hop across the pond your best source is often church records. Baptisms, marriages, and deaths were frequently recorded by the church and no one else. Sometimes these records would be destroyed for any of several reasons, all of them bad, but sometimes they survived. There are also tax records, if the ancestor owned property. But if you’re doing your family’s genealogy and your family has been here for a while, it’s good to stick to the American side of things and get that part sorted out before trying to track down what your ancestors were up to overseas. That’s been my experience, anyway.

Record keeping in what would become the United States wasn’t exactly orderly, but it is a walk in the park compared to whom your relatives were in 1350.

Add to this the fact that not all sources of information are considered sufficiently reliable to be taken as definitive. Gravestones with dates are good, especially those which contain their own miniature family trees, as of course are family graveyards. (We used to have a picnic on Memorial Day at the Cummings graveyards in Perry County, Indiana after we had cleared away the brush and replaced the American flags from last year.)

Census records can be helpful. Military service records can be golden. (For instance, I know that my great grandfather was docked a month’s Civil War pay for some offense; one day I hope to find out what it was he did.) Church records can be useful, but there can also be problems because in the olden days churches were sometimes not the dedicated, in-service-forever places we often think of today. I know what my paternal grandfather, James Ulysses Powell, was raised a member of Deer Creek Baptist Church. I have visited that church and have pictures of it. The current church doesn’t much resemble the place from my memory. I have no idea if they have any records of my grandfather and his ancestors, but I’d bet not.

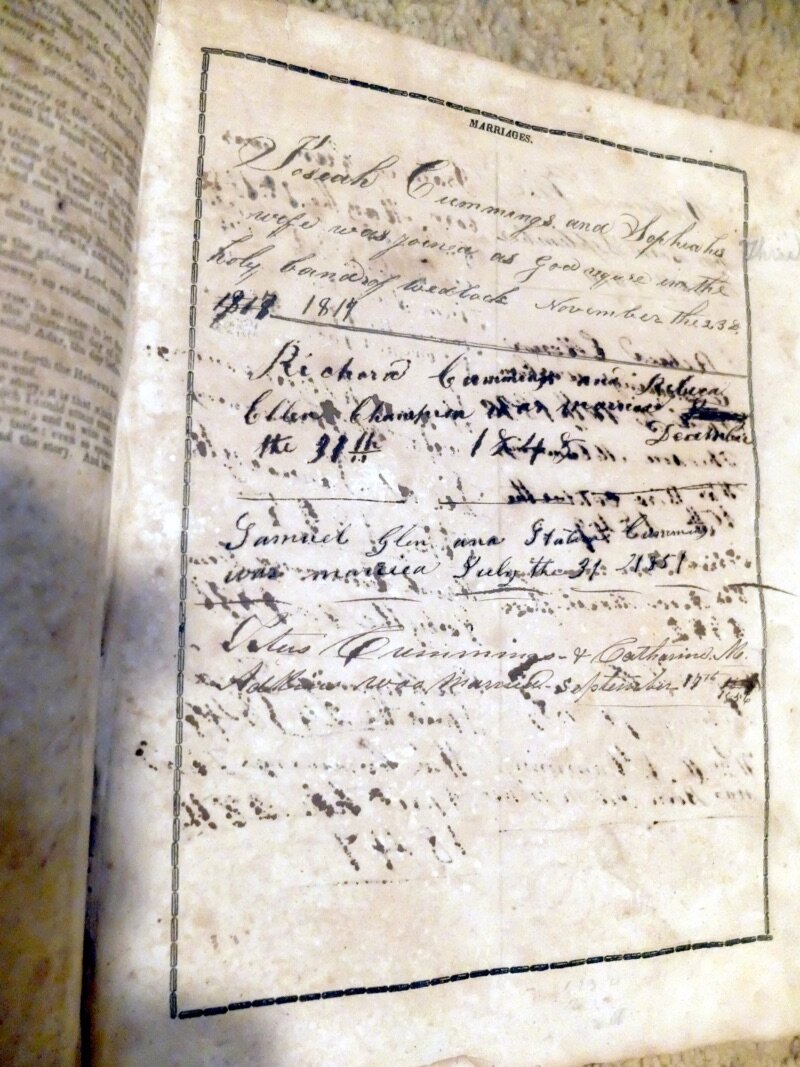

There’s another source that is generally considered reliable: the family Bible.

I do not know if family Bibles are still kept, but once they served the function that government statistics agencies serve now. Births, deaths, marriages, baptisms — these were dutifully inscribed in the family Bible.

When my sister asked how to assemble the evidence needed for her DAR application, I first searched, of course, online. Within five minutes I’d determined that great-great-great grandpa Thomas Cummings had already been recognized by that organization as a bona fide Revolutionary War soldier. I was sad to see he was only a private — I know we have higher ranks, but Thomas is the easiest apple to pluck from the family tree — and the same genealogical data that certify him also list his family. Among his sons was Josiah Cummings, who was father of Titus Cummings, my great grandfather. Titus was father of Laura Ann Cummings, who married James Ulysses Powell, and after 15 years gave birth to their only child, my father.

Now. We knew all of this already, but proving it?

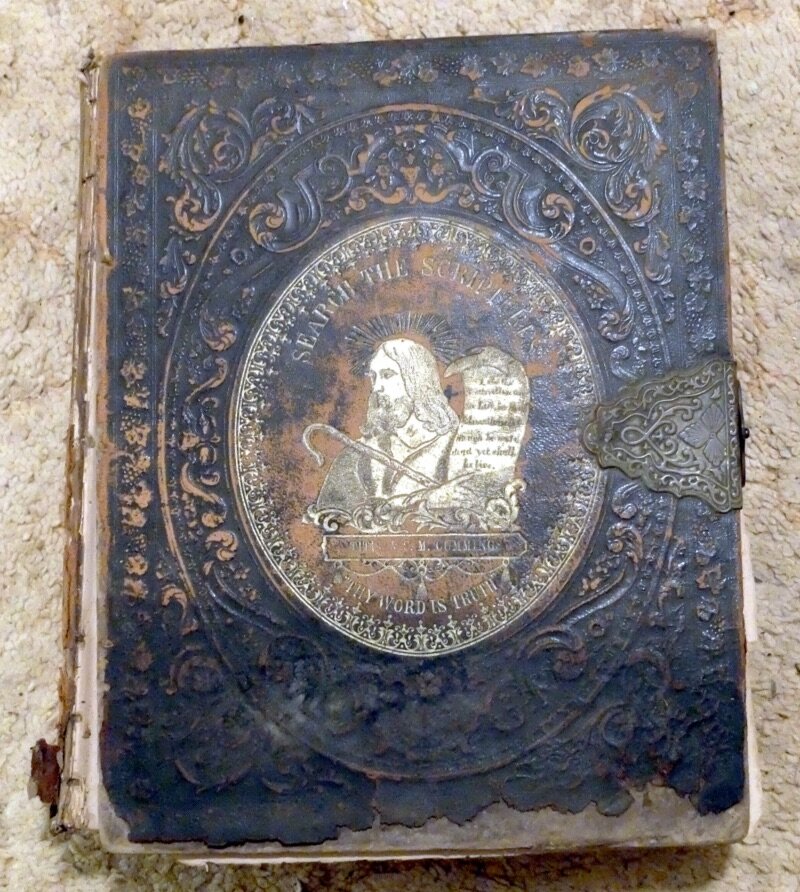

In a big, glass-fronted lawyer bookcase on the second-floor landing in my house reside many old books. I am sad to say that some are much the worse for wear after a half century at my mother’s home in fungus-filled Florida. On the bottom shelf, valiantly trying to avoid disintegrating entirely, are three family Bibles.

They are very big. They have pages bound in between the Old and New Testaments for the recording of family Bible things.

I carefully picked up the first of them, and opened it. Inside the heavily bound front cover, in florid, enormous letters, was written “Josiah Cummings’s Book.” Happy day!

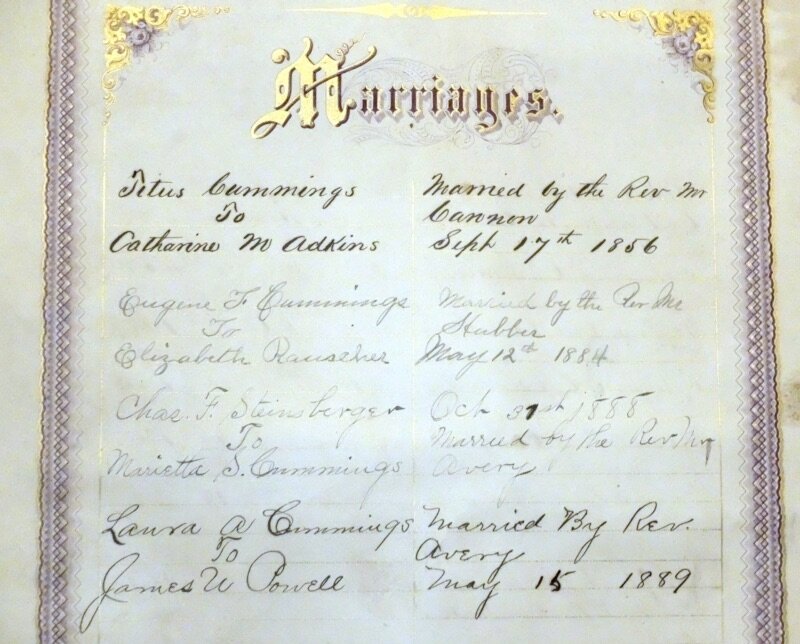

Though the center pages show evidence of having been wet at some point, the “Marriages” page shows Josiah’s marriage and that of their son Titus. Another page records Titus getting born.

Another family Bible, probably belonging to Titus, records the marriage of Titus and Catharine Adkins — and the marriage of their daughter, Laura, to James U. Powell.

Those Bibles are the proof of lineage my sister needs, I hope. I made photographs (some shown here) and sent them to her. My father’s own death certificate attests to his parents having been James Ulysses and Laura Ann Powell. So all my sister needs is a copy of her own birth certificate, which should be readily available.

All to prove what we already knew.

I got something more. I got to handle and look at pages that my ancestors two centuries ago looked at, handled, and wrote on. (I also discovered that our family Bibles are Catholic Bibles, still containing the books that the protestants had ripped out of their version of the Bible centuries before. Were they, except for my father’s father, Catholic?)

It was an exciting few hours. Solving family mysteries is a delight, as is proving the solutions, which is what I needed to do here and think that I did.

We’re a year away from the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence (and the 200th anniversary of the amazing coincidence of the deaths of two of its authors, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson). It’s a good time for everyone to take up genealogy. You don’t have to join any online clubs, despite the many companies that want you to do so. There is good free software that lets you keep track of your findings, though the program I use, Gramps, takes a little time to get used to. (It is powerful and also free.)

If you take up researching your family history, please follow this advice: go sideways not lengthwise. By this I mean gather the information on your grandparents, then all four of your great grandparents, then all eight of your great grandparents, and so on. Complete each generation before moving on to the next generation. The urge is strong to dive in and follow one line as far back as you can go. I made it past Charlemagne and was proud of myself until I realized that I had followed one tiny twig very far. (Also, everyone in the western world is descended, over and over, hundreds of times, from Charlemagne, so my proof proved, really, nothing.)

Every generation in retrospection doubles in number. You have 32 great-great grandparents, 64 great-great-great grandparents, and so on. The farther you go, the likelihood of finding someone amazing increases and the likelihood of the relationship being remarkable diminishes. And as you go farther back it becomes less about your family than a census of everyone who ever lived, because after not too many generations you discover that you are descended from everyone.

So go generation by generation and get a sense of your place in history.

Having family Bibles helps. As does reading them.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation