In the early part of this century there was an imaginative musical ensemble, the Trachtenburg Family Slideshow Players.

They were a father, mother, and young daughter. They would go to thrift stores and flea markets and buy up all the old photographic slides they found there. The slide boxes or trays sometimes contained notes as to what the pictures were, sometimes not. If there were descriptions, they might or might not be included in the fanciful songs the father, Jason Trachtenburg, would write about them. At their performances, the mother, Tina, would project the slides on a screen while Jason and daughter Rachel would sing the songs. Sometimes the result was kind of cute.

I’ve been doing much the same thing lately, though it doesn’t involve slides, writing songs, or performances, and the images I’m using aren’t from junk shops but instead from family archives. Nor am I projecting them for an audience. And I have neither wife nor daughter, which does uncomplicate things.

Emilie, the younger of my two sisters, a week or so ago sent me a big bundle of photographic negatives. They had been squirreled away by our mother, who died in 2007. That was all any of us knew about them. So it became my happy task to scan them and produce useful image files from them.

I had done this before with such family archives as I possessed. That time it involved hundreds and hundreds of negatives, slides, prints, and some old tin-types (which are a real bear to convert into usable images, but I somehow prevailed though I do not remember how). It had been years since I scanned anything, because my Epson scanner had broken. That was okay at the time. I had scanned everything that needed it.

But now this trove of, well, no idea what. Thus began a project.

First came fixing the scanner. I’d turn it on but it showed no signs of life. Going to sleep last Thursday night it occurred to me that the power supply was perhaps flaky. The next morning, even before coffee, I went to my all-purpose storage room and fetched the power supply from the spare scanner. (Yes, I have a spare scanner, an earlier model.) I plugged it into the newer Epson Perfection V550 Photo — and it fired right up. Problem solved.

Or so I thought. Silly me.

The last time I had used the scanner was several operating system upgrades ago, to scan the cover of my friend Pat Murphy’s book. There is scanner software for Linux that works with Epson scanners. It is called XSane. It can be made to work, and I set about making it do so. It was not a total surprise that I succeeded. Soon I was merrily scanning in the 50 or so photographic prints included in Emilie’s package. My mom had apparently sorted the pictures of her children, so those pictures Emilie sent were primarily of me. They were not of much interest, but I dutifully scanned them, anyway.

Then came time for the negatives. The scanner has an ingenious, if not especially efficient, way of scanning slides and negatives. Like a photocopy machine, it has a moving bar under the glass that contains the sensor and a very bright light, for use in scanning “reflective” things such as paper. But for transparencies, where the light must shine through, there is an additional light source, found under the removable pad that holds reflective stuff flat. Remove the pad, put the negatives in a (special, inconvenient, flimsy) holder and this light moves along above, sending the transparency’s image to the correspondingly moving sensor below — the original light remains dark — and the transparencies are scanned. It’s complicated, but that’s basically how it works.

Except that XSane has no provision for doing transparencies.

In the past I had used the original Epson-supplied, Windows-only software, running Windows in the Virtualbox “hypervisor” (a stupid term for a program that lets you run other operating systems under Linux), which does feature the ability to scan transparencies. It was all still installed on my machine. Except that now it didn’t work.

I’ll spare you the details — I would like to have spared myself the details — but it took a day and a half to get sorted out. I asked around online and, as is typical, I was advised of ways to do something else, up to and including why did I want to scan old pictures, anyway? The one potentially useful bit of information I got was of the existence of a program called “Vuescan” that, my correspondent said, would do what I wanted and would run under Linux. It seemed promising until I discovered that it costs $149. Things would have to have gotten pretty desperate for me to spend that much. If it had been $50, I’d have gotten it; $75, probably. But $149 — forget it. So it is good that I got the old Windows XP virtual machine finally to work with the scanner and the Epson software (which, I must admit, is pretty good). The Windows 10 VM never did work, but it sucks even more than XP anyway. Let me mention that words cannot express how much I hate Windows, any flavor of Windows.

It would be nice to say that you just stick the negatives in, push the button, and all is well. But niceness doesn’t begin yet. There are settings. First, I had to tell the software I was scanning negatives. Then I had to tell it the resolution to use. Your printer probably prints at 300 dots per inch. So when you’re scanning a document you’d print the same size, you set it to scan at 300 dots per inch. But negatives are small. A 120 negative, which most of them are, is 2.25 x 2.25 inches. A 35mm negative is 1 x 1.5 inches.

So I had to calculate the largest I, or anyone in the future, would ever want to print any of the pictures I was scanning, then multiply that by 300, the number of dots per inch scanned, to preserve the detail in the images. The possibilities go clear to 12,800 dots per inch, rendering enormous files that would take forever to scan. I decided to settle on 3200 dots per inch for the 120 film and 4800 dots per inch for the 35mm. This would allow 120 prints up to 22 inches square, and 35mm up to 16 x 24 inches before quality would begin to decline.

Then came something called “bit depth,” which is simply how many shades of gray are possible. The choices were 8 and 16. The former offers only 256 shades of gray, so 16 it was. I should mention that when you tell the software that you’re scanning a negative, it renders a positive image.

Now I was ready to start scanning!

The plan is to scan them all. I know what’s of interest to me, now, but I cannot guess what will be important in the future. As anyone who has ever done anything worth doing can attest, 20 percent of the pictures consume 80 percent of the work. I can pop in a strip of negatives, the software finds and names them, and three pictures are done in five minutes. But my father for a long time seems to have used a 2.25 x 3.25 Speed Graphic (or a 4 x 5 with a special back), employing film packs. These rendered individual negatives, not strips, that need to be loaded and scanned one at a time, which is an enormous pain. And though the software supposedly recognizes negatives of that size, that turned out not to be true, so I have to individually crop them to the image. Now we’re talking 10 minutes per picture. It would be easier if I skipped the difficult ones — but what might I miss? I was scanning everything and saving the scans. Even the trash. There is plenty of trash. (I didn’t curse even the 2.25 x 3.25 negatives; instead glancing over at my own camera that shoots that size film, a fine art-deco Busch Pressman here in the office. It wasn’t until this week that I knew my dad ever had such a camera. Must be genetic.)

Early color film — Kodacolor — looked awful and scanned with a terrible greenish cast. It scanned fine in grayscale, though, so I did that. Fortunately, there’s not much color stuff. So far.

I’ve been at it now for a little over four days and have scanned in 405 pictures, so it’s running about 100 pictures per long day. I would estimate I’m about 10 percent done. But you know what? That’s fine. This is craft, not manufacturing. When I find a picture of special interest, I email a scaled-down version to my sisters and sometimes to old friends who share an interest in photographic things, and a couple to cousins who keep the family torch burning. It’s a joy, even if it involves occasional grumbling. As one picture or small group thereof scans, I look at the ones just completed.

I was happy to discover one of the best pictures I ever took, in my estimation, of little Emilie at I’d guess age 4, running away from home, our dog Lucky accompanying her. It confirms a long-standing suspicion, that my mom secreted away the negatives of my favorite pictures. I’m hoping to discover more, a few in particular, negatives I’ve sought for decades and had given up for lost.

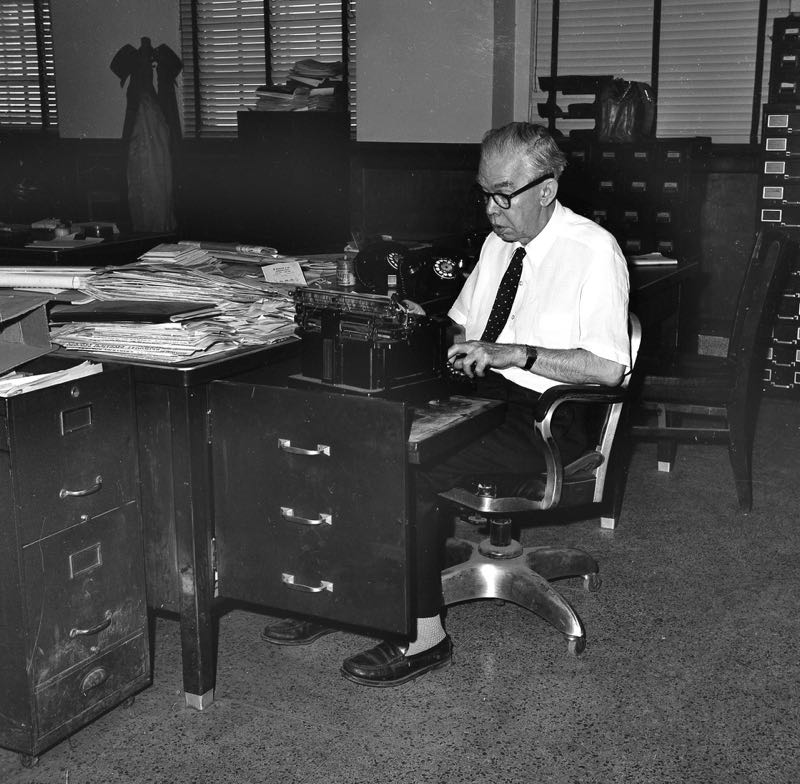

We can’t see into the future, and neither could the people in these pictures. No one at the time wold have guessed that at some point everyone would have powerful computers capable of sucking the images off the film, the very film in their cameras, and sending them around the world in seconds. Ours was a publishing family, so we knew about ways of distributing pictures as miraculous in that day as computers are now, such as the Fairchild Scan-a-Graver which each day turned my dad’s pictures into a form fit for printing in that afternoon’s newspaper. The time between artists having to make engravings of pictures and the time these negatives were made was no greater than the time between the pictures being made and now.

The project has resulted in tremendous surprise. I’m learning things about my family I had forgotten or never had known. I grew up in a house with three mounted deer heads in the room we called “the den.” Now I know about the Ozark hunting trip in October 1951 on which they were harvested. The son of a reporter and photographer — many of his professional negatives are in the batch — I tagged along on many assignments, but it wasn’t until now that I realized that I spent a lot more time at fatal car wrecks than other kids did, probably. And I can look at the changes in fashions, while also trying to figure out who many local Columbia and Jefferson City, Missouri officials were, important then, largely forgotten now. (I am sorry to say that I have proof that neither my mother nor my grandfather, her father, could take a good picture if their life depended on it.) I’m getting to know people who were old when I knew them, only now I have a sense of them when they were young. Stories I heard when I was little are coming to life, and I’m finding new stories I never knew. I can look at my dad’s pictures of my parents’ first Christmas together, before life and children had worn them down. I’m happy not to rush through all of that.

I’m discovering that I like them. All of them. And I’m reminded that the worst pictures are those nobody bothered to make. So if there’s a drawer of yellow Kodak envelopes in your family, with negatives inside, get a scanner and get at it!

Or you could get your older brother to do it.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation