The time has come. The inevitable can be postponed no more.

I’m switching my desktop computer to Debian Linux.

I should have embraced Debian from the beginning. Please allow me to offer my excuse for not having done so 26 years ago.

In 1997, when IBM basically put OS/2 to sleep for reasons that had nothing to do with its customers — nothing IBM ever does has customer satisfaction as the determining criterion, best I can tell — I needed to switch to a different operating system. Windows was not, as it continues not to be, a reasonable choice for anyone who considered a computer more than just another household appliance. The internet, and especially high-speed internet, was growing. A new word for most of us, “security,” would become an ever-greater concern.

Yes, I could have wrung a couple more years out of DOS, perhaps running the then-excellent GeoWorks GUI atop it but with other, serious applications available in text mode, the way anyone with a working brain ran Windows 3.x. (Windows 95 was a joke, and Windows 98 was a joke that didn’t even try to be funny.)

By January 1998, it was time to try out Linux. This was a bold move for someone who needed a computer to do work.

The resulting madcap mayhem would make a book. No one would buy it, but I’d enjoy writing it. Let me try to set up some guardrails so I’ll mostly stay on the road. Maybe I’ll display the view over the cliff some other time.

In 1998, one could download a version of Linux, burn it to a CD or many, many floppies, and proceed. The problem was that even on very fast dialup this would take forever. The way to get Linux was to go not to the software store but the bookstore, where one plopped down $50 and bought a thick book with a CD in the back. The CD contained Linux.

The books had goofy titles: “Red Hat Linux 4.2,” “Caldera Open Linux 1.1,” “Debian Linux.” What did this mean? Which was the one I wanted? Which was the Linux I’d been hearing about?

I asked around online, in strange places like RIME and UseNet. The responses were there were many “distributions,” of which Debian was best — if I could get it installed and configured, which I probably couldn’t. Looking more for a working computer than a learning experience (famous last words), I went back to the store, and based on a careful scientific study of the blurb on the front and the pictures on the back, returned home with a $50 book about and including Caldera Open Linux 1.1. I popped the CD in the machine, fired up the new hard drive — I wasn’t going to nuke OS/2 just yet — and after an hour of trying to figure out things the installation program incorrectly assumed I knew, I had booted to a command prompt, not the beautiful desktop promised on the back cover of the book. I felt as if I had bought a new house and on the day I was to move in arrived to find a pile of lumber, bricks, pipes, and spools of wire.

I booted back to OS/2, went online and asked about it, and learned that after logging in with username and password I might want to type “startx.” Which I did, and now I had a proprietary desktop called “Looking Glass,” a very cheesy Windows 3.x lookalike.

After a while I was persuaded to get Red Hat instead. The conversation always contained the advisory, “Debian is better, but you’ll never get it installed.” Red Hat did not include Looking Glass, so I had to cobble together a GUI from many parts, until that summer, when KDE 1.0 was released.

Over the next few years I rotated among Caldera, Red Hat, and a European distribution called SuSE that had a chameleon as its mascot. They were fundamentally the same, with the odd impressive “killer feature” here or there. For instance, one included a full, paid-for edition (it claimed) of StarOffice, the brilliant German office suite that over the years evolved (or devolved; opinions vary) into Oracle Open Office, OpenOffice, OpenOffice.org, and, leading the field today, LibreOffice. (It wasn’t the paid-for edition. It was the same demo version you could download anywhere.)

Also, the distributions themselves became weirder. Red Hat floated a stock offering, shortly before the dotcom bust which I think resulted from the decision to remove the hallucinogenic drugs from the water coolers at brokerage houses.

[Space here to insert paragraphs about the AI bust, which hasn’t happened yet but will.]

Red Hat soon decided that its flagship product would no longer be free. The stuff that made it Linux was still free. Red Hat didn’t own it. Nobody did. What you paid for was the installer, the program packaging system, and in my case the book.

Caldera, my first distribution, got even flakier. A guy named Darl McBride took over, and in short order became the most hated man in the software world. He claimed that Caldera owned all of Linux and every Linux user must pay him tribute. (Many lawyers grew rich, at least on paper, over McBride’s litigious antics, which were unsuccessful. McBride now runs Shout! Factory TV, which many of us have watched for up to a few minutes.)

SuSE, best I can remember, hadn’t yet done anything egregiously objectionable when Ubuntu hit the scene.

At about the time Google (“Don’t be evil”) was considered the good guy among the search engines — yes, children, it’s true; as with Satan, Google was not always evil incarnate — a distribution called Ubuntu hit the web. A guy named Mark Shuttleworth and a bunch of Debian developers had made a distribution, named for some African word or so it was said, that was basically Debian, only easy! It was the good guys of distributions. (Ubuntu would follow Google into infamy, as we shall find out.)

So in 2004 I switched to Ubuntu. It was as advertised. Every distribution has its quirks, and Ubuntu was no exception. Every year there are two releases, one in April and one in October, so this year there has been one called 2404 and next month there should be one called 2410. It is updated with security and other features constantly. The 04 releases in even-numbered years are labeled LTS, for long-term support. Users discovered that it’s best to let a LTS version steep for a year, get the bugs shaken out, before installing it in an odd-numbered year. But it was fine otherwise.

Then Shuttleworth and his merry band went the way of so many others: it began to ooze slime. It switched its package management system — extremely important in Linux — from the standard Debian .deb packages to an effectively proprietary format called “snap.” The user was given no choice in the matter. This locked in the user to Canonical, Shuttleworth’s company, for his software.

It also installed, off by default at first, spyware that phoned home to tell Ubuntu what you were up to. There was some strange connection to Amazon built in, too. This seemed easy to disable or uninstall, so many of us put up with it.

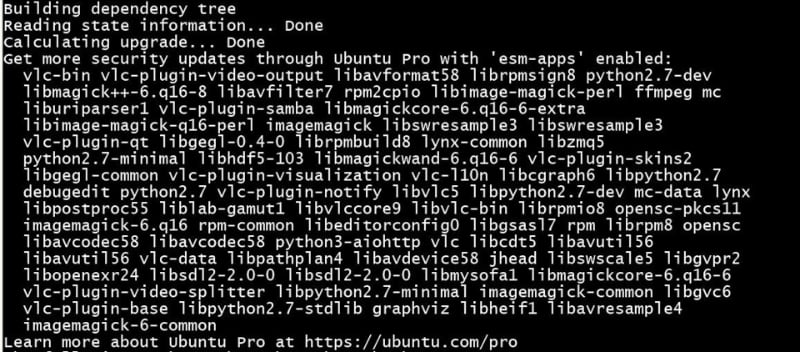

It then sprung upon us something called “Ubuntu Advantage.” Among its delightful features, when you update/upgrade your software for security purposes, it holds back some of those updates unless you sign up for Ubuntu Advantage.

My first thought was that Shuttleworth might think of starting a streaming channel called “Whisper Workshop” or something. My second thought was that I wanted to get the hell away from Ubuntu. Saw this show before, didn’t like it then, not likely to like it now.

I should mention that none of this is a stunning discovery. It has been going on for years. There appear to be workarounds for some of it, ways to defeat the Canonical-Ubuntu spyware. I’ve employed them, and yet I see that “ubuntupro” was logging things as recently as this month.

The real stunning discovery is that while I wasn’t looking, Debian, the premier kind of Linux, got easy to install and configure. Really easy. The old fear-uncertainty-doubt spread by other distributions is no longer true. More than two decades of anti-Debian prejudice can be cast aside.

Like so many things that shape modern computing, indeed, like Linux itself, Debian was cooked up by a college kid. In 1993, undergrad Ian Murdock released the first version of the distribution, 31 years ago this month. His girlfriend (later wife, then ex-wife) was named Debra. Hence Debian. Debian software packages have the suffix .deb. Cute, just the tiniest bit cringy, and God-level nerdish. (Murdock died a suicide in 2015; his reason, if known, has not been made public.)

Once it was installed and running, Debian was always the Linux by which all others are measured. Many Linux flavor-of-the-month distributions such as Mint (and yes, Ubuntu) are based on Debian. (My favorite teeshirt is as one from “Progeny Linux Systems,” a company Murdock started to sell a tricked-out distribution. I got it at Linux World Expo in 2001. I have one and you don’t, and that makes me cool.)

One of the complaints about Debian was that it was so tied to the free-software religion (“free as in speech, not free as in beer” is the phrase everyone uses and no one understands) that any hardware that required proprietary drivers was not supported. This rather significant obstacle to adoption has now been set aside somewhat, and you can download Debian with “non-free” software included. You specify which version you want when you download it. There is an ideologically pure version available also.

My first Debian installation, of the current Debian 12 “Bookworm,” was on my lovely old Thinkpad a few months ago. I was surprised: It couldn’t have been easier. It is as easy as any Linux installation out there. (You may wonder about the “Bookworm” name: Debian distributions are named after characters in the “Toy Story” series. As I said, cringy and maximum-nerd.)

For the notebook installation I was happy to wipe the whole hard drive and install from scratch. That’s not the case with my desktop machine, which has some fairly elaborate configuration files going back to 2004. I am not certain I could recreate them all, but I’m entirely certain that I do not want to try. So throwing the contents of my hard drive into the air, sliding in Debian, and hoping the other stuff comes down correctly will be tricky.

The answer, I think, is installing a nice, new hard drive. The 16-terabyte Toshiba enterprise drive has been out for a while and is well-regarded, yet it is not over-the-moon expensive. I ordered one (and was amused to see that the very next day its price went up by $100, so getting closer to the moon). The plan is to install the drive, unplug the existing drives, and install Debian. Then I’ll plug in and mount the other drives and copy data, configurations, and so on to the appropriate partitions on the new drive. It will be methodical and annoying and will take a couple of days, but at the end I’ll have a nice new fast Debian installation, and I will lock away the old drives as backups. There are a few applications that for security reasons can’t just be copied over, so I’ll need to do them from scratch, but that’s fine. (Of course, it’ll be a week before the new drive arrives.)

Then everything in the house, even the television sets, will be running on Debian.

And with luck I’ll never have to change my Linux distribution ever again.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation