Overloaded with politics and the contemptible collection of low creatures whence we must choose come November, maybe it is time to discuss something good and decent and pure: Snakes.

As I was leaving for the store yesterday I noticed that a black rat snake had gotten into the basement. It’s not the first time it has happened, though not always in the basement and not always a blacksnake, and I doubt will be the last.

It saw me and slid, as they do, back among a stack of things one keeps in the basement utility room. Unconcerned, I went to the store.

Back from the store, I opened the door and the snake was right there. I grabbed a stick and pulled the snake toward me — I was outside — and pretty soon it was gliding, as snakes do, toward the woodpile. I won’t be surprised if it comes back a time or two, so the process is likely to be repeated. It seems to think there’s food — mice — inside my house. It is probably right.

Snakes get a bad rap, always. I suspect that this comes, first, from the Book of Genesis. I have no experience with talking snakes. I have lots of experience with the other kind, which are all beneficial, even the poisonous ones unless you behave stupidly around them.

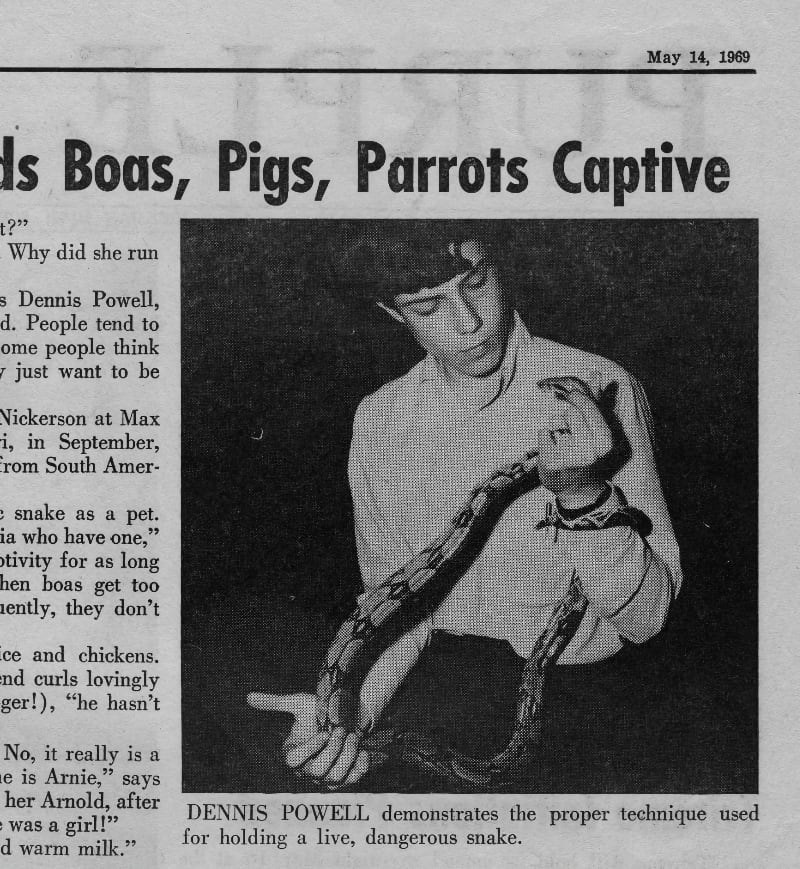

It was my good fortune growing up to be taught by my dad and by the great Max Nickerson, and from them I learned a great deal. Among those lessons was the importance of referring to living things by their scientific names. There are several reasons for this. For instance, especially when it comes to snakes, a given species might have a dozen common names, so the scientific name pinned down what it was you were talking about. More important, if you knew a thing’s scientific name you often got a good clue as to its place in the taxonomical swing of things.

Here’s an example. The blacksnake, also known as the black rat snake, the chicken snake (and, in the account given to me by a local idiot, the “six-foot rattlesnake”), was known to me as Elaphe obsoleta obsoleta. There is also the gray rat snake, Elaphe obsoleta spiloides, the yellow or four-lined rat snake, Elaphe obsoleta quadrivittata, and others. Their genus is Elaphe. Their species is obsoleta. So, though the three I’ve mentioned are widely different in appearance, they are sub-species — races, as it is sometimes put — of the same thing. This means they could intergrade, or cross-breed. I do not know the extent to which this happens in the wild, though I do know it happens at least some of the time. There are other species within Elaphe, the best known probably being the orange Elaphe guttata, or corn snake. A different species, it doesn’t cross breed with the others.

(Lately the taxonomists have changed a lot of these names, for reasons not entirely clear. There aren’t a lot of new snakes being discovered, so I guess they did it to have something to do. But it’s annoying.)

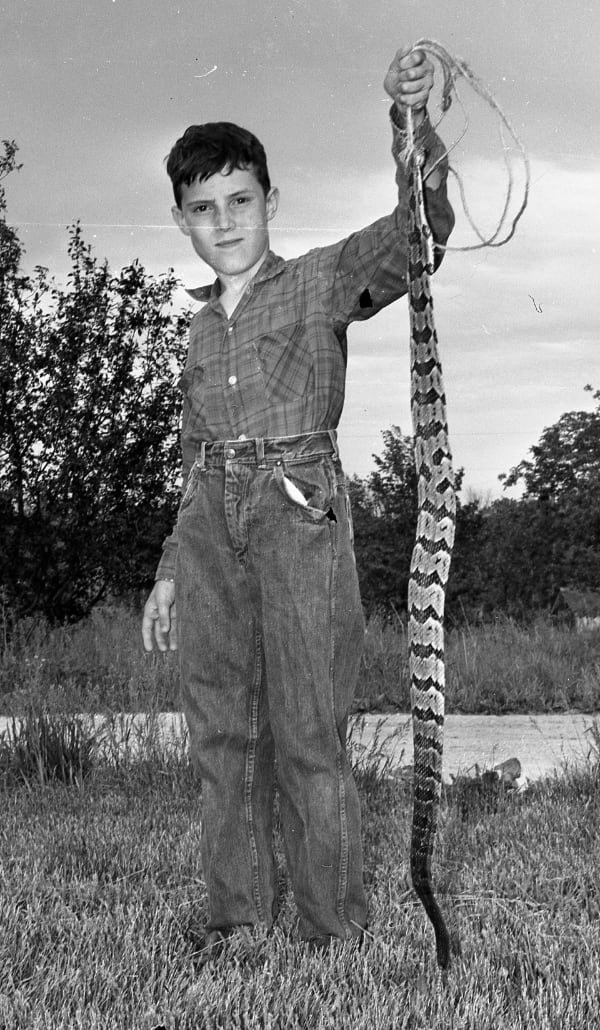

Growing up I lived in a place that had timber rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus), massasauga rattlesnakes (Sistrurus catenatus), pigmy rattlesnakes (Sistrurus miliarius), and copperheads (Agkistrodon contortix). So we had poisonous snakes. (Many people swore we had cottonmouths, a/k/a water moccasins, but we didn’t. And seeing any of the venomous snakes we did have was pretty uncommon; I saw, and sometimes caught, fewer than a dozen of them, and I was looking for them.

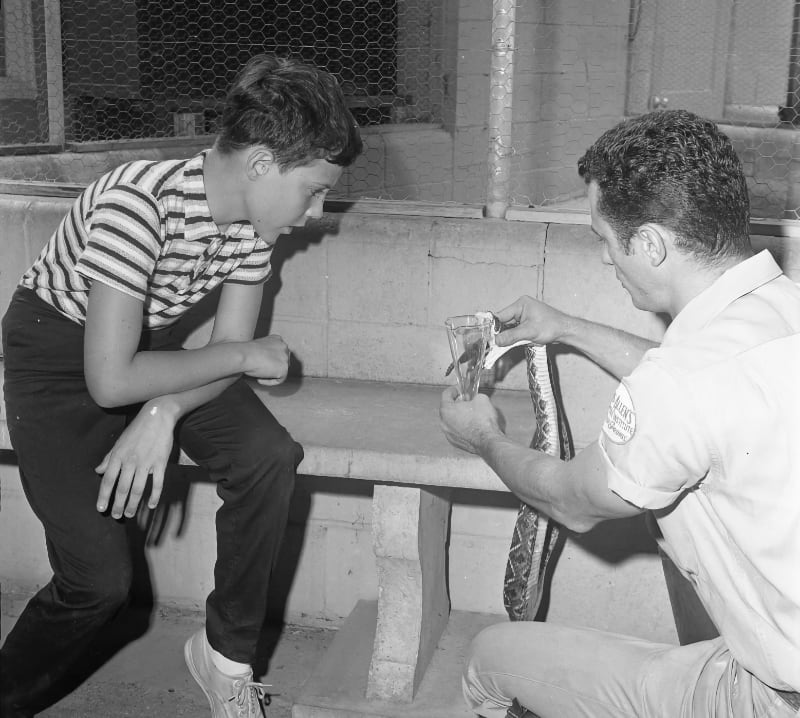

As a kid whose family often vacationed in Florida, I would catch a lot of local Missouri snakes before we headed south each summer. The reason for this was that every small town in Florida had a local reptile collector, and I could do trades. (Also, a family friend, Jim Miller, worked at Ross Allen’s reptile exhibit in Silver Springs, and he would load me up with Florida snakes and turtles to bring home.) One year, a Florida snake hunter traded me a baby rainbow boa for a small speckled kingsnake I’d brought for the purpose. The baby rainbow was tiny — about the size of one of those big pencils we had in first grade — and it was difficult to find baby mice to feed it. Then, as sometimes happened, it got loose in the house, in the middle of the winter. I looked for it, unsuccessfully. Ultimately I figured it had crawled someplace and died.

Several months later my sister Emilie was going up to bed one night. She came down the stairs and said, in a bored, slightly exasperated voice, “There’s a snake on the stairs.” It was the baby rainbow boa, now the diameter of a broomstick and three feet long. It had apparently found its own supply of mice. (My sisters could tell you many such stories.)

The stories can go in many directions. In January 1968 I was up all night after hearing on the radio that my friend and snake-hunting buddy Ed McDaniel had been bitten by Max’s black mamba. The standard assumption then was that if you are bitten by a black mamba — so named because while it is itself a nice pastel green, the inside of its mouth was inky black — you would die. Ed didn’t die, not then. A few years later he was riding a bicycle to work when a truck hit and killed him.

In Florida I later watched a show given by the famous Bill Haast of the Miami Serpentarium. My impression was that Haast, dressed like the mad scientist from an early horror movie, was a dangerous clown well deserving of the disregard in which he was held by serious herpetologists. While I was there a blue krait slithered off the table where it was being shown and slid through the assembled spectators. It was caught before it bit anyone — evidence that even very deadly snakes are more interested in getting away than they are in biting. Also at the Serpentarium, a 6-year-old kid fell (how?) into a crocodile pit and was killed. Haast shot the crocodile — and then put its skeleton on display for paying customers. For all the invariably positive press he and it got, his whole operation seemed pretty rinky-dink to me. He claimed to be the only man to have survived a bite from a king cobra. I was more interested in people who could handle king cobras without getting bitten, a fairly easy skill to master. And people who could show a blue krait without turning it loose in the crowd.

Even as a kid, I thought it was my obligation to correct misconceptions about snakes. There are many such misconceptions, especially in rural areas — city dwellers aren’t worth correcting. Many farm people thought snakes were bad and should be killed. It was a losing battle, though I think I convinced a few people that the best way for them to deal with snakes was to leave them alone.

When I moved here almost 20 years ago, the local plumber tried to warn me about garter snakes, often incorrectly called “gardener snakes.”

“If you’re growing tomatoes, you’ll go out and see how they eat half of your tomatoes,” he explained. Being polite, I stifled my laughter. This was a situation where a missing piece of evidence led to the wrong conclusion. It was easy to see how it happened: a gardener went out one day to look at the tomato crop and saw that one had been gnawed to pieces. Over there, enjoying the warm morning sun, was a garter snake, all fat and happy after having had a meal. It was clear what had happened.

Only it wasn’t. Garter snakes don’t eat tomatoes. Snakes aren’t herbivorous. Instead, the tomato had been eaten by a tomato horn worm. The worm, in turn, had been eaten by the garter snake. The evidence thus gone, the gardener assumed the snake had eaten the tomato.

The fact is, almost anything you hear about snakes is wrong.

Which isn’t to say I was always above a little showmanship. From time to time I would take a snake to school to show my classmates. I would talk about the natural history and habits of the particular snake. (I never attempted to frighten anyone with a snake. That’s wrong, if your goal is to help people understand and accept them.) I had come to own a very big Arizona gopher snake. It was entirely docile, but I had discovered that if objects were passed back and forth in front of it, it would become alarmed and would strike at them. I took it to school, talked about it, let those who cared to do so hold it. Then came the stunt. I blew up a balloon, red if memory serves, and waved it in front of the snake. It drew back and struck. Its small but very sharp teeth did what you’d expect, and the balloon popped loudly. It was pretty impressive.

No circus phoned to hire me, however.

By far the coolest snake one might encounter is the hognose snake, Heterodon platyrhinos. Hognose snakes eat toads. That’s all they eat. If you’ve ever poked at a toad you’ll remember their habit of puffing up to look bigger and more fearsome — and to be harder to swallow. Well, the hognose snake has specialized, long teeth in the back of its mouth, to do to toads what the gopher snake did to the balloon. But that’s not what makes them cool.

When disturbed, the hognose spreads itself flat and hisses loudly, trying to look as big and dangerous as possible. But it’s all for show. Though it seems to be striking, it moves its head rapidly backwards, the opposite of a strike. No one has ever been bitten by a hognose snake.

If this elaborate show doesn’t work, it dies.

Well, not really, but it pretends to die, impressively. It rolls over on its back, its belly skyward. If you pick it up, you’ll find it entirely limp. But if you turn it over so it’s right-side up, it immediately turns back onto its back again. If you wait, very still, in a few minutes it lifts its head up and looks around; if the danger is gone, it turns over and goes about its business. It’s the favorite snake of everybody who knows it.

Okay. I could go on about snakes for a few hundred pages. They’re fascinating. They do not have business with you, so they are no threat if you don’t mess with them. With slight precautions — don’t turn big rocks or logs without looking first, for instance, if you’re in and area where poisonous snakes are common — even the poisonous ones pose no particular danger.

I’m still possessed of a desire to protect them from the falsehoods told about them.

So when you hear a politician described as a “reptile,” a “snake,” or a “viper,” quickly reject it.

Snakes are not malevolent, aggressive, or evil. So likening them to politicians is unfair to reptiles, snakes, and vipers.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation