Shortly after I turned 4 years old I ran up to my favorite cousin, Alan, to show him my new cowboy boots. I neglected to consider the implications of the fact that he was at the moment driving our new Montgomery Ward riding lawnmower and as a result — entirely my fault, Alan’s sense of guilt notwithstanding — came within an inch or so of having my left foot lopped off. As it was, my big toe had to be pretty much surgically reattached by Dr. Horace Thomas and there was a long cut across the bottom of my foot. The cowboy boot was beyond repair.

I remember more of it than you would imagine, and it’s a gripping story (to me, anyway), but for our purposes now it suffices as explanation of why soon after I turned four my foot was in a cast. Which is how I got my first pocketknife.

During my convalescence my dad took me along on his various tasks, which one day included a trip to Rackers & Baclesse, the local lumberyard. One of the owners, Buell Baclesse, was moved by my plight and gave me (not “gifted,” gave) one of the little penknives the company had by the cash register for, I think, $1. I was very proud of this, and was temporarily pleased with the bargain — you could go after me all day long with a lawnmower if I could have a pocketknife! (We are more focused when we are 4 years old.)

At age 4 I couldn’t actually open the thing. My dad took it for safekeeping and said I would have to wait until I was 6 to carry it. (I couldn’t open it then, either: the springs holding its two blades were very strong, and the tiny nail nicks never did give me sufficient purchase to extract either blade.)

Last week while looking through some small items, I found that knife. It had been poorly stored at my mother’s place in Florida for decades. Its liners and blades are carbon steel, and the very air in Florida is destructive to steel that isn’t stainless. So the knife is rust-welded to itself. I’ve soaked it in WD-40 and in due course I hope to get it cleaned up. I wouldn’t except that I could see the “Rackers & Badlesse” name and the company’s five-digit telephone number stamped into one of the scales, which for some reason made me smile.

I found it while looking for something else in the course of trying to repair my two (one two-cycle and one four-cycle) TroyBilt “string trimmers” — weed whackers. A day into it I was beginning to conclude that the company did not intend for either of them to be repaired. Anything more than replacing a spark plug and you’re supposed to replace the whole thing, I think.

No. I refuse.

Things should be fixable and we’re obligated to know how to fix them. Not everything, perhaps, but small gas engines and many small electrical devices, absolutely. Replacing washers in faucets, entire toilets or parts thereof, an electrical outlet. These are among the things we should know how to do before we own any of them. Sharpening knives, lawnmower blades and scissors. Changing a tire. Basic skills.

Not many years ago, every town in the country had a fixit shop, a place where you could take items — an electric fan in need of a new cord, a lawnmower that just wouldn’t start, a toaster that no longer toasted — to get them repaired for far less than the price of a replacement. Those are mostly gone now. (Where I live, the local independent hardware store served much the same function, but during the pandemic they sold out to a big chain, and that service no longer exists. The old man there, who knew every part of everything and how it worked, has I guess retired.)

Corresponding to the disappearance of those businesses came an overall cheapening of consumer products, both as to price and as to quality. Many of us remember when the brand names “Black & Decker” and, worse now, “Bell + Howell” meant something, carried a certain cachet. The former was the maker of high-quality power tools, the latter of the industry standard movie-making tools for news gathering. Today, I have a Black & Decker rice cooker, and if you want you can buy cheap Bell + Howell plastic rechargeable sidewalk lights from ads on late-night television. Products are no longer meant to be repaired. They’re now intended to be replaced when they break, which is alarmingly frequent.

Again, no.

Which is why I was on the back porch with three different kinds of screwdrivers — flat, Phillips, and Torx (the last, developed to keep us from taking things apart), working on the engines of the TroyBilt machines. I had to replace the primer bulbs (little rubbery domes to prime the carburetor with gasoline, so you don’t expend all your energy just getting the thing started), the gas lines (which lead into the most inaccessible part of leaky plastic gas tanks) and gas filters, air filters, and spark plugs.

I must claim a degree of success, with the 4-cycle machine. It now starts right up and shuts right down, in about the time it took me to type this sentence. It has gobbled up carburetor cleaner to the extent that it’s a good thing — one of several reasons it’s a good thing — that I won’t be fathering children, because I’ve inhaled enough exotic hydrocarbons that my genes are probably close now to those of a space alien. I’ve tried everything I can think of. It starts and then it stops.

Finally I broke down and ordered tune-up kits for both of the machines. These include a whole new carburetor, gas lines, fuel filters, spark plugs, primer bulbs, and related parts — all for $15 total. That seems mighty cheap, but in my experience Chinese preschoolers do good work. I’ll replace the carburetors and keep the other things as spares, because sooner or later I’ll need them.

I have an $800 Generac backup generator. In order to mollify voters in corn-growing states, our politicians have decreed that fermented corn juice be included in our nation’s gasoline. This causes a lot of problems, but because these problems frequently result in replacement of mostly new machines with brand new ones, manufacturers don’t much complain. (If you think this means that your concerns are at the very bottom of the pecking order, you’re absolutely right.)

Among the problems caused by ethanol contamination of gasoline is electrolysis in the carburetor. If you do a web search on leaking Generac carburetors you will find that it is a common occurrence. The carburetor float gets corroded and stuck to its chamber and can no longer move, resulting in gasoline being spewed all over the place. When a generator is needed, people are not typically in the mood for such foolishness. Leaked gasoline can turn a blackout into a blackout and fire (and if you are in the territory “served” by Frontier Communications, you won’t be able to call the fire department when the power is out). When my Generac machine started spewing gas I packed it up and sent it off to the company. After a few weeks it was returned. If they did anything at all, it was not reflected in reduced gasoline leakage. So I got a cheap Chinese carburetor online and installed it and the Generator has worked perfectly ever since.

Generac ought to be ashamed of itself.

As should our educators. There used to be classes in high schools that offered instruction in useful skills. As I understand it, these have largely disappeared, and at least one generation of helpless, skill-free graduates has been the result. Ignorant consumers, the manufacturers’ dream.

Our only savior, and I have to take frequent puffs of oxygen from a tank to make it through this sentence without passing out from the ridiculousness of it, is YouTube.

You buy a new implement. Inside the box there is all kinds of entirely useless literature and, down there in the corner, the instruction manual, folded into a little wad the size of a postage stamp and written in print of the size used in those tiny novelty Bibles that used to be sold, which could be read only with a microscope. (You’d get them from the same fascinating catalogs that had miniature spy cameras and hollowed-out beans stuffed with a dozen tiny real ivory carved elephants. Each of these items, including the Bible, was $1.)

Anyway, you get out the magnifying glass and unfold the wad of instructions. You discover that 90 percent of the instructions came from lawyers, in hope of reducing the lawsuit judgment if you cut off your fingers (or toes) with the thing. The remaining 10 percent is approximately this: “1. Take out box. 2. Start up. 3. Have happy life now.” The same thing is then repeated in several different languages. It’s amazing how much you can fit on a 4-inch-by-6-inch piece of very thin paper.

So we must resort to YouTube. I recommend looking at videos about your device from several different people, because some YouTubers have no idea what they’re talking about. Spend half an hour viewing the relevant videos and you will have seen whatever you’re trying to fix from several different angles. You’ll have learned which things are important and which are just the crotchets of the presenter. You’ll have achieved a degree of comfort with the project without having yet lifted a tool.

It certainly made my job far easier when I turned the Generac generator into what it should have been when it left the factory — reliable and safe — and thanks to the metallurgical superiority of slave-labor children I no longer must fear the dark.

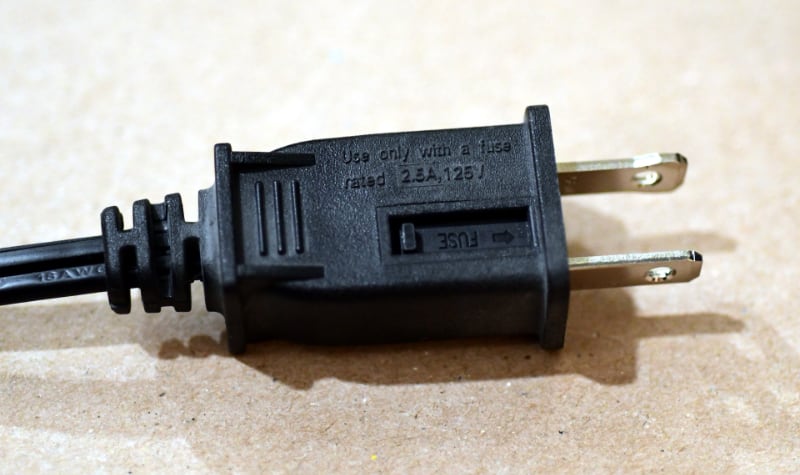

Even when you manage to purchase an implement or appliance said to be repairable, the maker might throw you curveballs. An example is the vortex room fans sold by Honeywell (another name that has coasted over the last few decades, in my estimation). One day you will turn it on and nothing will happen. I believe that at this point you are supposed to throw it away, but as I said previously, no! So you go online and you discover that you probably blew its fuse.

But where is the fuse? You wouldn’t find it if you looked all day, so after an hour or so you go online and learn its peculiar location: It is in a tiny drawer built into the thing’s plug! Is there the slightest chance that you have a replacement fuse, or can find one locally? Well, it’s not impossible, but it’s pretty low on the likelihood scale. So you try to get a replacement online and within two or three tries there’s a slightly better than even chance you’ll get the right one. By which time you’ll have replaced the fan anyway because it’s summer and its hot. Or you might have just replaced the plug with one that doesn’t have a fuse, which probably isn’t recommended.

Many of us have supported the “right to repair” campaign, the movement to enact laws that say we own the things we bought and therefore should be able to fix them when they break. (It is their vigorous opposition to this idea that has caused me to decide never to purchase a product from the John Deere company.)

But based on what I’ve seen, manufacturers tend to respond to a right to repair by making their products impossible to repair. Even if you know how to fix your car, you don’t have the special dealer-only tools required, for example.

Which manufacturers see as reason to buy new products, and I see as reason to keep what you have, maintain it well, and learn how to fix it if it breaks, because the new stuff is even less reliable and more cheaply made.

Even if it is an ancient, cheap, advertising pocketknife that’s rusted shut.

The old, wise, saying goes, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” But the inverse applies, too.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation