It is as familiar a phrase as any in American English, usually remembered in the smooth baritone of Nat “King” Cole: “Chestnuts roasting on an open fire . . .”

The song was written by Robert Wells and Mel Tormé in 1945. (The first line made more sense then.) It is secular, as Christmas songs go — both Wells and Tormé were Jewish — but it acknowledged that yes, this is a religious holiday.

At that time, even now to a small extent, people would have known the meaning of that opening line. Roasting chestnuts was a seasonal activity, the way making hot cider is come the first chills of November. It had been done for centuries here and abroad. In big cities, streetcorner vendors offered still-warm, freshly roasted chestnuts for sale to festive (or hungry) pedestrians. It was this practice that would lead to the near-extinction of the then-common chestnut.

Chestnuts do not store well. They’re ready in late autumn, so November and December is when they’re best consumed, hence their association with the Christmas season. (Chestnut stuffing for the Thanksgiving bird is also popular, or was when American chestnuts were available.)

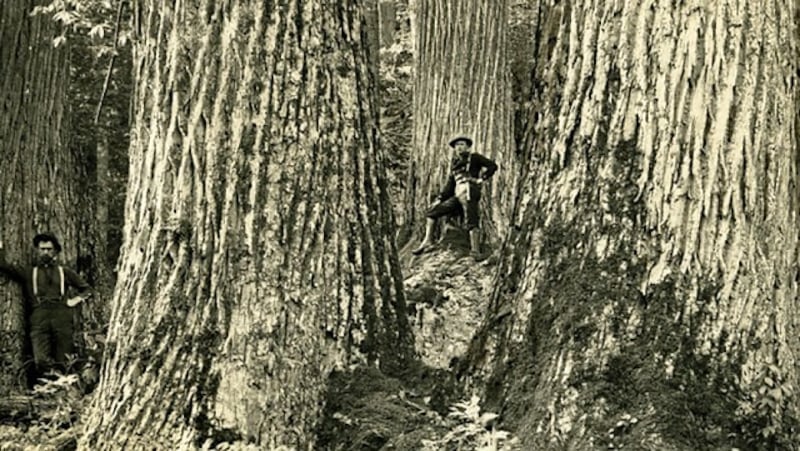

A century and a half ago there was no tree more common in the woodlands of the eastern United States than the chestnut. It was the biggest tree around (though there were beech trees that got nearly as big), and it was essential to the lives of people who lived where it was found. Its wood is highly rot-resistant, so homes, fences, barns, and just about everything else were made from it. The Appalachian poor would gather chestnuts for shipment back east, where they would be roasted and sold. Farmers would loose their hogs in the woods in the fall, to fatten up on chestnuts before going to market.

Like many — all? — nut trees, the nut part is encased in an outer covering. With walnuts, it is a strong-smelling husk that will stain your hands and clothing dark brown; with hickory and beech it is woody. The chestnut’s outer covering is spiny, like a sea urchin. Those spines are sharp! The whole thing is called a burr, and if you’ve ever encountered a cockle burr or a sand burr, then meet a chestnut in its natural state, you’ll know how appropriate the name is.

Is poetry — real poetry, not insane gibberish — still taught? There was a time, and I hope we’re still in it, when every child knew this line and the ones that followed: “Under the spreading chestnut tree, the village smithy stands.” (By the way, “smithy” is the correct word for a blacksmith shop, not a familiar endearment of the blacksmith.)

The chestnut was a very important tree. But then . . .

Around the beginning of the 20th century — the exact villain has never been identified, nor the date of the offense — Chinese chestnut trees were brought to the United States and Europe. The nuts they produce are larger than those of the native American chestnut, though the trees themselves are smaller and bushier and less useful for anything other than growing nuts.

Unbeknownst, we hope, to the importers, the Chinese variety also carried a parasitic fungus. The Chinese trees knew how to survive it, but American chestnuts were defenseless. The fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica as it is now known, gets under the tree’s bark near the ground and works its way around, preventing water from getting to the branches and leaves above and sugars from getting to the roots below. Over the next half-century, the American chestnut tree was essentially wiped out. There are pictures of “ghost forests” made up of dead chestnut trees, their bony white trunks reaching skyward, the bark fallen away but the wood, resistant to rot, still standing. By the 1950s, the chestnut trees were gone.

It was a huge ecological disaster. It continues to be a huge ecological disaster. Those abundant nuts fed woodland creatures, not just pigs. Acorns and hickory nuts, the food that remained, weren’t and aren’t enough. The American chestnut didn’t go extinct, but for all useful purposes it did. (Shoots still spring up from the roots of trees that have been gone for a century, the result being a plant that’s not much more than a bush, usually, before the fungus gets it.)

All this is of particular interest to me because there is in my yard an American chestnut tree, bigger than a bush though scarcely towering, that is mature enough to produce chestnuts. It is spindly and no more than 20 feet tall — it’s only about 25 years old — but it’s there. The tree is located on a very steep part of the yard, so harvesting its spiny nuts is dangerous.

I wish I had more American chestnut trees, more conveniently located. Is it possible? Maybe. It’s too soon to tell.

In my RCIA — Catholic catechism for adults — classes 15 years ago one of my fellow converts was an Ohio university student involved in development of blight-resistant chestnut trees. He said I could have some seedlings if I wanted. (My property is an officially registered tree farm.) I planned to get and plant some, but then didn’t. Recently I looked into it and discovered that the problem isn’t entirely solved. There has been work crossbreeding Chinese chestnuts with American ones. Progress is slow because it takes decades to find out if the experiment was successful. There is a single tree someplace in New York that seems to be resistant, and pollen has been harvested from it and used to impregnate other trees, though in what may be a first actual care is taken until it is known whether the tree has undesirable characteristics, too.

There is also work being done in genetic engineering that might impart immunity to the fungus.

Let me pause for a moment to say something about genetic engineering, whose promise and dangers have both been exaggerated by people who have ulterior motives. Genetic engineering is like fire. It can be put to good use, or it can be destructive. It has no values of its own. It is foolish to say, “Yippee! It’s genetically engineered!” and it is foolish to say, “Oh, no! It’s genetically engineered!” How to handle genetic engineering responsibly is as yet unestablished. On one side, there are surely those who would employ it irresponsibly, to make a quick buck. On the other side, who should set the standards? Chin-stroking academics? Pfizer? Tony Fauci? We can only hope it is worked out over time, as many other things have been.

I do not know what the “resistant” seedlings offered to me a decade and a half ago were. My sense of it is that they would probably all be either dead now or illegal. But I cannot know.

In poking around a little I’ve learned that there is a lot of work being done in hope of reintroducing the American chestnut to forests where once it thrived. There is an organization, The American Chestnut Foundation, that keeps track of it all and sponsors some of it. The organization offers hybrid seedlings for sale and, I’m alarmed to say, seeds for what appears to be $75 apiece. (Though I suppose you could trade your family’s lone milk cow for one. Fee-fi-fo-fum.)

Even if good seedlings were readily available and even if I planted some, I would be long gone before they would achieve the towering majesty of the chestnut trees that stood in my woods a century ago. In a way it is sad: though those of my generation have seen many marvels, we’re doomed to be one of the (few, one hopes) generations that lived during the time there were no chestnut trees. But we might now make sure that future generations will enjoy what we missed.

It is to be hoped for, as is my resolve to harvest next year’s burrs from my chestnut tree at just the right time and next Christmas enjoy the extremely rare treat of roasted American chestnuts as our ancestors might have had them.

I wonder if Wells and Tormé had any idea in 1945 that both the first and last lines of their song would describe things that would fall into grave danger. Having now spent a thousand words arguing in promotion of the subject of the first line, please let me now offer my heartfelt support of the last line.

Merry Christmas to you.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation