The conversation with my friend Angelo was satisfying and thought-provoking, as they always are.

We had been talking about how men, when they grow up (chronologically) and have money, are wont to buy the things they desired but didn’t get when they were little boys. A kid who wanted to collect all of the Hot Wheels dinky models might now spend thousands of dollars to complete the set. No, more than complete the set — get them all in their original packaging, untouched. It costs thousands of dollars because there are many boys-now-men who have the same idea.

There are variations, modernizations, such as the fellow — Angelo sent a picture — who has collected all but two of the variations of the Spyderco Dragonfly pocket knives, and he was desperate to find the other two. They have over the years come in a variety of colors, and one can’t help but think that when each new color, or variation in steel formula, or special marking is released, Spyderco counts on purchases from guys determined to collect the entire set.

(This kind of obsession is in my experience less common among women, though they are not immune. Consider the insane Beanie Babies fad of a few years ago [and apparently now]. I have a big box of commemorative silver spoons collected a century ago by my own grandmother, the sanest woman in the world. So it’s not entirely chromosomal.)

The conversation turned to something I jokingly asked my friend Jeff a few years ago: Don’t you wish you still had everything you’ve ever had? A wiser person would have added, And a place to organize and store it all? We agreed that yes, indeed, we would. We were talking about cameras, either when I asked the question or soon thereafter, because for photographers they are the mechanical items one loves the most.

Well, not loves but loved. It is difficult to love the plastic contraptions cranked out today, which are triumphs of marketing.

In a decade, no one will remember what it felt like to make a picture with a modern Nikon digital single-lens reflex camera, introduced a few years ago and already on its way out. But I will always remember the tactile delights of my old black Nikon F: the feeling of the shutter release, how the dot atop the shutter release shows the release button revolving when the film is advanced, how the film advance feels. It is not not the smoothest in the world but it is robust and reliable. It is the Colt 1911 of 35mm cameras. Introduced in 1959, it remained in production until 1973 — about six generations of cameras in today’s modern digital world. (Don’t believe me? Look at the latest and greatest digital cameras of 2009!) When you see pictures of the 1960s riots or the Vietnam War, chances are they were made by a photographer using a Nikon F. I still have the first one I ever owned, which I purchased for $150 from a National Geographic photographer in 1968, after he had used it in Vietnam for a year or two. Kind of beaten-up when I got it, it still works perfectly. It has never been to the repair shop, either.

If you have ever owned or just held and used a real Leica M-series camera (M-3, M-2, or M-4), you have its mechanical delights burned into your very soul. The way it feels to trigger the shutter of an original, two-stroke-film-advance M-3 is the very definition of exquisite precision. (That model was so superbly made that its hinged back door had tiny, spring-loaded balls that corresponded with detents in the camera body to make certain the pressure plate that positioned the film was exactly positioned.)

Those of a certain frame of mind — I am among them — think that these qualities alone justify having them and keeping them, just to appreciate them and the days when they were used every day. They use film and and do not provide instant gratification, so they are not practical for the “workflow” of photography today. But something very important got lost with the change. A 1959 Nikon uses the same film and lenses and makes the same pictures as a 1995 one. Digital camera picture quality changes model-to-model.

Such reminiscence might be dangerous, a sign of one shuffling into the dimming light. But let’s embrace it for a few minutes, anyway. There’s surely no harm in that.

“It's a sad digitalized world we live in now,” Angelo said. “I'm even more sad that they have things like what Google has been advertising on their new phones - the ‘Best Take’ photography. Where it replaces your ‘bad takes’ with only the ‘best versions’ of the photos you've taken. So it's automatically photoshopping pictures for you.

“Very sad in my opinion.”

The curse of everybody’s favorite subject they know nothing about (other than politics), artificial intelligence, is that soon we won’t even need processing tricks. Soon you will be able to ask your phone to produce a photo-realistic picture of Jesus and Satan both bowing before Donald Trump, and it will do it. So, no surprise, those motivated by money and power are selling us a new way to lie. There’s always a market for more efficient falsehood. I remember big debates, back when serious people discussed serious subjects, over whether it was ethical to retouch an unattractive power line out of a picture of a building (and when a news photographer’s membership in the human race required him to put down the camera and help rescue the family from the burning station wagon). Now it is no longer what we should do, but what we can do.

The zen of photography disappeared when film fell out of common use. It was a contemplative pursuit, photography — especially news photography — was, back when it was art. We’d call it “method,” if it were acting.

“I miss processing film,” I wrote Angelo, in our Signal exchange. (And if you do not have Signal, get it, dammit!) “There is nothing that matches the exquisite isolation of being in the darkroom making prints, working until it is just right. It is like being in a different universe.

“Plus, when you have experience, you have your own little tricks: leave the hardener out of the quick fix for faster and more thorough washing. Use selenium toner on all prints, not just the warm-tone ones (on cold-tone paper it makes the blacks very deep). Use Photo-flo before drying the film and Pakosol before drying the prints. Photo-flo means you don't have to squeegee, while Pakosol does something good for the print but you use it because it smells so good. I doubt that any of this is even made anymore. [Selenium toner and Photo-Flo still are; unfortunately, Pakosol seems to be gone.] Good photo paper is more than $1 per sheet, and I sometimes go through 25 sheets before I have it just the way I want it. Alas.” (I must confess that the selenium toner trick came from the great David Vestal, in one of my favorite books, The Craft of Photography.)

Making pictures was my passion beginning the week my father died, when I was 13. He was a reporter and photographer; during his terminal illness I made the pictures for his newspaper outdoors column, which he continued after infirmity precluded his other duties. After he died, I spent every spare minute in the photo department at the paper, and before long I was being sent on assignments, on deadline, for the well-known and photographically profound daily newspaper.

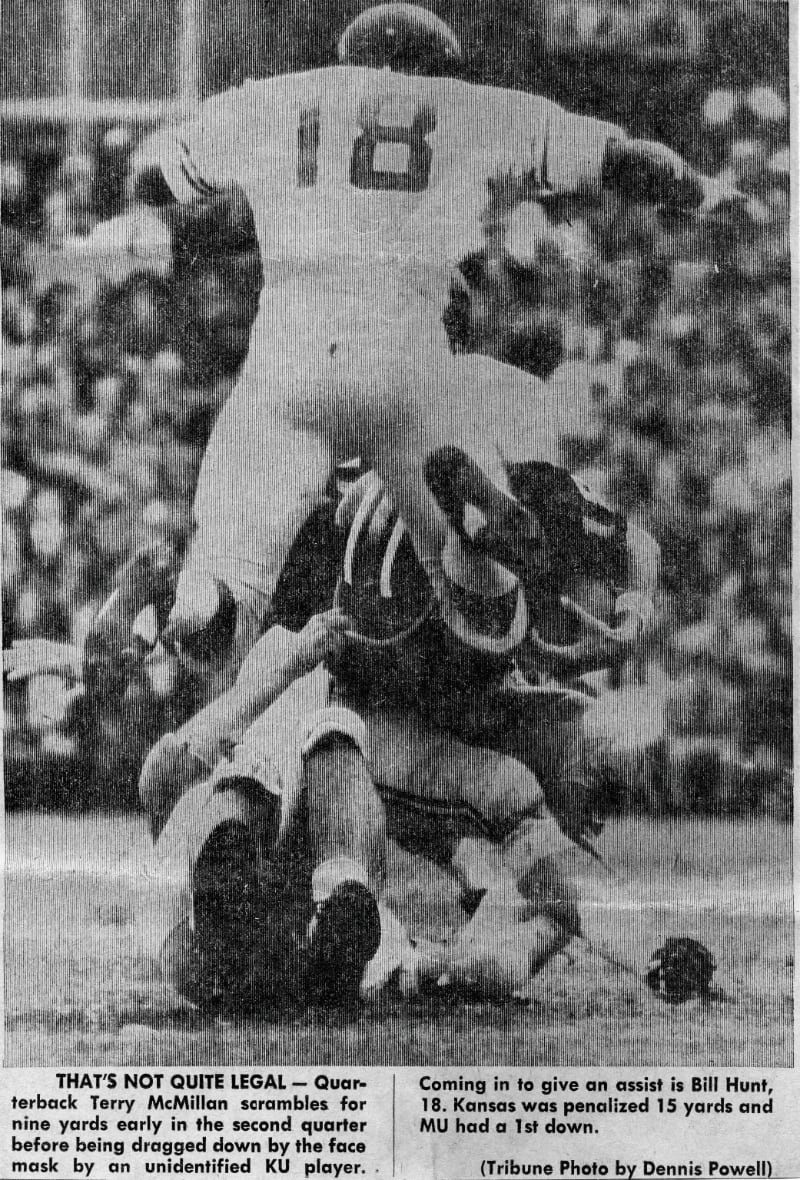

It was exciting. I was taught well by Keith McMillin and Earl Powers. (Earl was even more of a Luddite than I am: when he got a new camera in 1969, it was not a modern 35mm single-lens reflex but a brand new 4x5 Speed Graphic, though he did nod to modernity by putting a 120 film back on it.) They taught me the techniques and the chemistry but, more than that, they taught me the rhythm of picture making, especially in the darkroom. When you were working at your best, you and the job became one. Only very rarely have I encountered that kind of synergy, that zen, anywhere else.

“I have to give digital its due,” I told Angelo. “In the old days you would shoot the picture, zoom back to the office, process the film, if you're on deadline print from a wet negative, wash the print and dry it, and make the photo engraving, meaning that it was hard for something that happened today to be in today's paper.

“Now, 10 seconds after the picture was taken it can be on the editor's desktop, and the first hard copy is the newspaper itself. (I have had pictures on the newspaper's website within five minutes of making them.)”

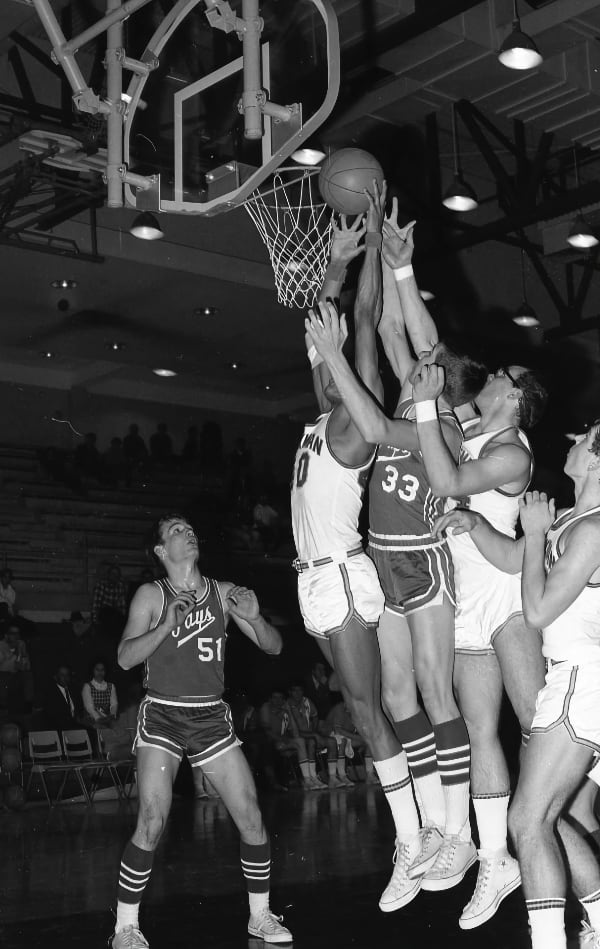

A good example of the old way was Friday nights, when I would be sent to photograph the all-important high school basketball games. The deadline was such that I could photograph only the first 10 minutes of the games before heading back to the office. I was too young to drive, so I had to walk very briskly the mile back to the newspaper office. Fortunately, basketball teams tend to be their most energetic during the first few minutes.

At the office, I’d go into the film room and process my film, often shot with Keith’s Rolleiflex — better for use with flash than my Nikon. Keith would usually make the print. Then, the next day, the miracle: a picture I made last night was in today’s paper. (Which was often delivered by me — I had a paper route during part of this time. There were no video games, so we were forced to develop useful skills instead.)

In later years, at other, bigger papers in other, bigger cities, I’d often stop by my house on the way from an assignment to process and print my pictures. The darkroom technicians did a good job, but only I could make the image reflect what I saw. As I said, there was a zen to it.

That’s not the case anymore, not with digital photography. Sure, you can do manipulations and tricks, you can use the “Magic Eraser” to eliminate undesirable objects and people. (We used to put in-laws on the ends of groups, so they could be cropped away if things didn’t work out, which was only slightly more honest.)

I more and more think of what in my earlier years I thought would be a dream retirement: Making very pretty black-and-white pictures with a huge 8x10-inch view camera, then make prints, 8x10-inch only, by contact printing those gigantic negatives. Photography at its purest. A good man could get in tune with that. Pure zen.

But I also know me. I had that dream long ago, when I couldn’t afford it. Which means I’d now get one camera and lens, then another, and soon would have a room full of beautiful old wooden view cameras, big brass-mounted lenses and a range of shutters, old, bulky tripods, a stack of original film holders, two pictures per holder . . .

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation