Next Tuesday is Halloween, though holidays are now moved all over the place. No doubt plans are underway to desecrate Christmas, New Year, and Thanksgiving, but moving Halloween all over the place is especially inconvenient, in that it involves strangers coming to our homes, so we must be there, and if it’s spread out over many days . . . well, you can see. Or will.

It wasn’t always like that. Let’s take a few moments and replace thoughts of unhappy now with happy then. What follows is my memory, from a rural community in Missouri; perhaps you have Halloween memories of your own.

I guess my generation was the last for whom Halloween's frights were based on the supernatural rather than the sociopathic. Crisp, moonlit nights were fertile soil for ghost stories. Of course, we didn't actually believe those stories, not really, though if we were out walking at night, and the wind suddenly died and it was now very still, there was a strong tendency to run like hell for home. But if something was going to "get" us on Halloween, it would be a malevolent force risen from the grave, not a razor blade in an apple or a needle in a candy bar. Or, now, someone with fentanyl.

In fact, Halloween was more of a festival than anything else. The crops were in. Such butchering as needed be done was completed. The first frost was lurking nearby, the Indian corn was dried, the "putting up" of fruits and vegetables was over, and in a farming community it was a rare moment of rest.

There were school Halloween parties. I don't know if schools still have Halloween parties, because the holiday does have a vague religious connotation, and we mustn't allow children to be exposed even vaguely to religion anymore, lest they turn out with some sense of right and wrong — we can't allow that.

Our Halloween parties were a lot like other parties at school. The entire day was pretty much lost; though teachers made an attempt to teach in the morning, the effort fell victim to anticipation of the afternoon's festivities. Each class had a few "room mothers." Room mothers volunteered to be responsible for class parties and the like. They'd come along on field trips, and they'd make cupcakes and punch for Halloween and Christmas and Easter. My school did not lack for parental involvement. PTA meetings were well attended and the parents all knew each other.

We would bring our costumes to school and, right after lunch, don them. It was never quite clear what this was all about — were we supposed to try to guess who each other was? That certainly took no time at all and, besides, we'd mostly put on our costumes right there, in front of each other. Most of the costumes were store-bought — garish plastic masks with cheap, fake-satin capes that had some image painted on them in glitter and bright paint — and really uncomfortable. They were viewed uncritically by us, though, even after they'd gotten gummed up with those sticky little peanut butter candies wrapped in orange and black waxed paper, and stained with pink punch (all punch, it seems, is pink, and, no matter the ingredients, tastes exactly the same). The bowl of wax-coated caramel corn was as full at party’s end as at the beginning.

There occasionally would be a departure, though, such as the year I went as a robot. My costume consisted of a series of gray cardboard boxes, elaborately attached to each other. It was difficult to put on, impossible to take off without help, and very difficult to move around in. It was a little too big, so I couldn't quite make out anything through the eye holes, and I kept bumping into things. It was impossible to get up if I fell down in it. And though I could turn my head inside the head box, the box itself didn't turn, so I couldn't see anything there, either. It was a good idea that fell far short in its execution.

At school, it was a disaster.

Parties comprised running around, being loud, and taking liberties with the sanctity of the hallowed place of learning. Among the sacrileges were blackboard eraser fights, which left large, yellow (the teachers at New Haven R-II School used yellow chalk and the blackboards were green) blotches wherever a direct hit was scored. A largely immobile gray cardboard robot was an easy target, and from my point of view, I had come not as a robot but as a bass drum. My costume did not want for resonance, which enhanced its popularity as a target for blackboard erasers.

It did not take long for this to lose its appeal to me. It was hot inside that terrible thing. Whose idea was this, anyway? Mine? Well, it's a parent's responsibility to say "No!" when a child has an idea as bad as this one.

"THUMP!" Another eraser. No matter where I went, I couldn't escape. "THUMP! THUMP!" There was much laughter now. I thought of the cartoons that show shooting galleries, with the little duck going back and forth. I knew now how he felt. And I couldn't even see in this thing! Only one thing to do — take the silly thing off. No straitjacket artist ever made more of an effort than I did now. "WHAM!" Boy. Somebody really wound up that time! This was awful! I tried to snake my arms backward into the big body box, but it would have required my retracting them straight into my body, a skill I lacked. I was starting to panic. "THUMP!" More laughter. I'm in a claustrophobic frenzy now, and they think I'm having a good time! Suddenly — oh no, I was falling down! I couldn't see anything. I especially couldn't see Irvin Whittler's tall, buckle-up snow boots. Over which I had just now tripped, breaking my fall only a little when a coat hook — I was apparently at the back of the room — clipped a shoulder of the main box, turning me on my back, like a turtle. The good part was that the fall dislodged the head box — knocked my block off, literally — so now I could look around and actually breathe! I was both pleased and disappointed to discover that I was not the center of attention. It seemed that most people in the room hadn't noticed that I'd been under siege at all!

Now that I had been well and truly vanquished and the threat of robot invasion no longer existed, I was left to recover on my own. And sure enough, I was able to slowly crawl out of that damned box.

I put the head box inside the body box and, later, carried the whole thing aboard the school bus. It was raining, so it got a little soggy and lost its shape, and because of its size, I had to leave it up front, near the driver, where it got mud-spattered and suffered further indignities. By the time I got it home, it looked as though it had very decisively lost a particularly fierce intergalactic battle. It was placed in the breezeway, the screen porch between house and garage. I never put it on again. That night, I wore an old sheet with eye holes cut in it, hoping no one would notice the floral pattern around the edges, and went as a ghost. A far more sensible costume for trick-or-treating.

And trick-or-treating was where the Halloween-cum-Harvest Festival began. It was one of the two or three major social events of our neighborhood's year.

Being a rural area, our neighborhood was spread out over a couple of miles. The immediate neighborhood was grouped around a quarter-mile square, owned mostly by us. At the south was Route AC, at the east was Rock Quarry Road, and the other two sides were a white gravel and asphalt road that had no name that I ever knew of, though when the area was annexed into the city the road was named Southland Acres Drive. We lived inside the square, on the north side. The south was mostly pasture, with our big pond next to Route AC.

Across AC lived Carl Hunt. His house had burned down a few years before, but it was quickly rebuilt. He had a tractor with a big hay wagon, and on Halloween night parents would bring all the neighborhood kids to the Hunts's house. There, we'd pile onto the trailer. Mr. Hunt would then take us from house to house — first to the Giesekes's house, then the McDonnells's, and so on. (I guess this was before the day when liability became a big issue. Nobody ever got hurt, but if someone had, I can't imagine anyone in our neighborhood thinking the situation could possibly be improved by the addition of lawyers. It was a different era.)

There was a wonderful etiquette to life in the country. When the porch light was on, visitors were welcome or at least accepted. When it was off, one knew to knock on that door only if there were a compelling reason to do so — cattle loose, a fire, that sort of thing. This code was Mr. Hunt's guide. Those families who welcomed an unruly group of children would leave their lights on, and off we'd go, to invade, grab our goodies, and continue our loot-and-pillage further along our route. It was important to be among the last to get on the wagon, because then you'd be the first off, and get to the victim while there was still a good selection.

One year, we approached my grandparents house, and I was shocked to discover something horrifyingly wrong. The porch lights were all different colors. Instead of nice, normal white light, the bulbs were giving off yellow and green. Ah, that's Grampa, I thought. Once he got an idea in his head, there was no shaking it, like the years he refused to switch to daylight saving time. He called it "Democrat time," and whenever he'd go to the bank during the summer, he'd arrive after the place had closed. So I figured he'd decided to change the light bulbs on the porch and, seeing that colored bulbs were the only ones he had, he'd screwed 'em in. But then, just as I'd completed this thought, the door opened.

There stood my grandparents, both normally so dignified (even if Grampa was a crackpot at times), both past 80 . . . and both wearing hideous masks! As we got closer, Grammy pushed her bridgework through the mouth hole in the mask with her tongue, wiggling the false teeth ominously. And once we got inside, we found the bulbs had all been changed there, too! It was so uncharacteristic, which made it all the more wonderful. My sisters and I were truly frightened; everybody else thought is was very funny indeed. By the next day, though, we were filled with new affection for our grandparents. We knew that they were wise and kind, and that my grandfather made a point of demanding that those around him use judgment (which, apparently, ran counter to daylight saving time) — but now we knew that within all of this they had room to have fun!

As soon as the marauding band had moved on, the occupants of each house would turn off the lights and drive to the Gregorys' house.

Rock Quarry Road was paved only to its intersection with Route AC. South of that, it was a bumpy dirt road, full of holes and washboards and a few places where the road's surface was the natural limestone of the terrain. The Gregorys lived on this part of the road, at the bottom of a hill so steep, winding, and treacherous that it could not be negotiated on bicycle in either direction. But once this menace had been traversed, we would gaze upon a well kept, sprawling lawn, the Gregorys's beautiful little cottage, and the stream that ran alongside the yard.

Mrs. Gregory was a home economist with the extension service at the University of Missouri — sort of a county agent to homemakers — and she appeared on Channel 8 and the local radio station regularly, which made her kind of the neighborhood celebrity. She was also one of the nicest ladies in a neighborhood chock full of nice ladies. She lived with her husband and their two sons, Jim and George, at this idyllic little farm.

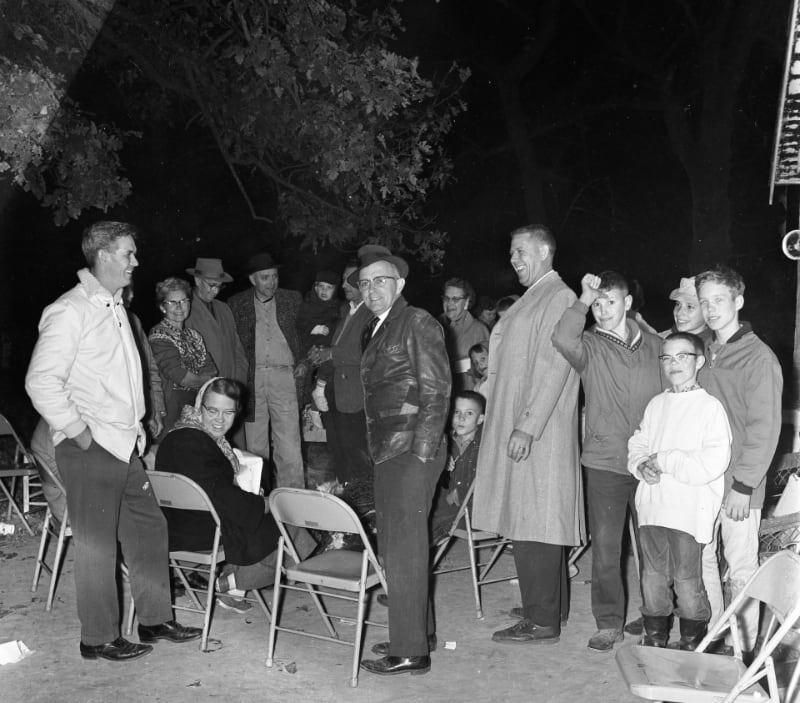

And every Halloween, after the kids had extracted their due from the neighborhood, everyone would gather at the Gregory home for a party. There would be a bonfire, and hot dogs and marshmallows, and pies all the mothers had made, and delicious homemade foods of all sorts. Such minor pre-adolescent intrigues as needed attention received it here, for it was a very romantic night. Even if the object of affection were not there, she was certainly thought of, and such thoughts would sometimes inspire acts of great bravery — such as the night I decided to walk home from the Gregorys', alone in the dark, up that awful hill and along the gravel road, Halloween night notwithstanding. I made sure that Susan McDonnell knew of my expedition, because she would surely make it known to one and all the next day, and my unexcelled heroism would be known far and wide. I would be gazed upon with adoration. Also, she was best friends with the object of my desires.

The walk, which was a little more than a mile and which I'd done during the day hundreds of times, took on epic proportions in my mind. I looked back at the crowd around the fire, heard the talking and the laughter, and rounded the first curve up the hill. The sound quickly faded, though the eerie dance of the light from the fire played through the trees, bringing the shadows to life, for longer than I was happy with.

(I am sorry to report that absolutely nothing eventful happened on that walk. I was very sorry the next day, too, that Susan didn't mention my walk home to anybody, except when prompted by me, as which time she offered the opinion that it was kind of dumb. She was, of course, right, because of the reason I had done it. Had I walked home because there is much enjoyable about a long walk in the country on a chilly night, it would have been anything but dumb.)

Those Halloween nights produced a kind of closeness I have not known among neighbors since then. It was a time when the kids got to have a truly wonderful time, and when parents renewed friendships, regained a sense of community, and realized once again that we were a solid group of people, people to be counted on when needed. (And who in my estimation had at least one heroic child.)

One of my most vivid Halloween memories, though, happened on a chilly, cloudy Saturday following that holiday. It's of my dad, building a fire in the fireplace, the first fire of the season. In place of kindling was some folded up gray cardboard that seemed to have been wet, for it had delaminated. Someone looking at would not have guessed what it had been, but I knew. I watched the flames consume the last yellow, chalky rectangle. And I smiled.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation