New technology and discoveries have improved our lives in many ways, but I wonder if we’ve paid for them in the things we’ve lost.

The question was raised through a bit of study disguised as entertainment — how it should be — I’ve undertaken lately. The issue is why it is that when I think of New York City, my first mental image entirely contradicts my years of living and working there.

Modern New York is not the place to be, not to visit, not to live. I have friends who do live there, but they’ve never known anyplace else. The son of a friend, which young man I’ve known since before he was born, has told me that he’s far more comfortable in the subway at midnight than he is out in the country at any time. I couldn’t understand it, nor could he imagine how I’m comfortable with the strange sounds emitted by the natural world.

I do not like New York or any other city. I appreciate their advantages, and when I’m forced to go to New York or some other — what’s the phrase? oh yeah — greater metropolitan area, I do my business and get out of there as quickly as I can. Cities do things to people.

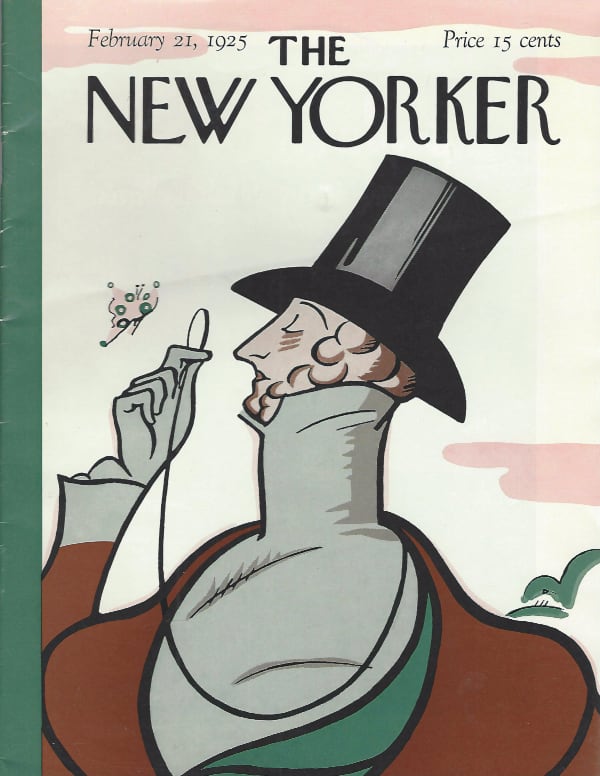

So why is my initial thought of New York City a pleasant one? Three reasons come to mind. In no special order they are The New Yorker, a game show called “What’s My Line,” and WQXR Radio. I’ll consider them now in that order.

The once-great New Yorker was above it all. I remember an airline flight through a long line of tremendous storms in the late summer of 1976. I would normally have been terrified, but I picked up a copy of the magazine that someone had left behind and was quickly engrossed in an article about sailing. I knew nothing about sailing, but when my ashen-faced fellow passengers, happy just to be alive, and I, just plain happy, arrived in Fort Lauderdale I was eager to sail. It had not been until I reached the end — New Yorker stories were back-signed — that I learned it was written by William F. Buckley, Jr. I wrote a letter to him. It would lead to a decades-long friendship and a decades-long passion for sailing. We even sailed together a couple of times.

Though even that was not peak New Yorker. I have a shelf of books, most of them purchased before I ever visited New York, that are about The New Yorker in the early days, and the people associated with it. They’re within arm’s reach as I write this: E.J. Kahn’s “About The New Yorker and Me”; James Thurber’s “The Years With Ross”; Moss Hart’s “Act One”; and biographies of various characters there and thereabouts, of Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, Dorothy Parker, and others. The New Yorker was inextricably tied to the Alqonquin Round Table, an informal daily luncheon gathering of the city’s finest writers and humorists in the Rose Room at the Algonquin Hotel. There are books about it, too: “Vicious Circle: The Story of the Algonquin Round Table,” and “Wit’s End.” They were among the funniest people and quickest wits who ever lived. As part of my recent study I watched an excellent documentary, “The Ten-Year Lunch; Wits & Legends of the Algonquin Round Table,”which you can watch, too, at the link. It all made me want nothing more than to go to New York and write for The New Yorker. It was the pinnacle.

(When I did get to New York, the possibilities had changed. Those wonderful people were mostly gone, though I met and sometimes worked with people only one step removed from them, and I occasionally had way too much to drink at Costello’s, where James Thurber had drawn cartoons with his finger in the wet plaster many years before. Before I moved to New York I had interviewed the actress Helen Hayes, whose husband, Charles MacArthur, was a member of the Round Table. I visited the old New Yorker building and I’ve had a drink at the Algonquin. You could still catch a faint whiff of something that had passed, something belonging to a marvelous bygone age.)

“What’s My Line” was a very popular television game show, from the early years of television until 1967. It was tied to The New Yorker and the Algonquin Round Table in that its panelists, especially in the early days, traveled in the same circles. For example, a frequent guest panelist was Kitty Carlisle, married to Moss Hart, mentioned above. The panel’s regulars shone with brilliance: Bennett Cerf, the founder and president of Random House, Arline Francis, the noted stage, film, and radio personality married to actor-producer and frequent guest panelist Martin Gabel, and, most of all to my mind, the quick-witted and brilliant reporter and columnist Dorothy Kilgallen. It was hosted by John Charles Daly, who had been a CBS reporter for many years. Patricians all, yes, but it was their brilliance and extemporaneous humor that carried the day. The ladies appeared in evening dresses and the men in black tie, with the exception of the broadcast following the (mysterious) death of Miss Kilgallen, which had taken place a few hours after the previous week’s broadcast. For that show the panelists dressed as if attending a funeral. The show was always the picture of genteel politeness. The men would stand to greet the guests. Honorifics were used. Daly would ask ladies who were guests, “Is it Miss or Mrs.?” The program was broadcast live. The panelists wold make (often very good) jokes that were also tasteful. Following the death of original panelist Fred Allen, the fourth seat remained open, filled each week by a guest panelist. These varied, from Peter Ustinov to Tony Randall to Broadway and film stars of the day. It was as close to the Algonquin Round Table as you could get without time travel. Fortunately, many of those original episodes were preserved, so you don’t have to take my word for it. And my sister Emilie’s godmother, Jane Froman, was the mystery guest on March 1, 1953.

(When I got to New York, I was able to make a little more of a connection. Arline Francis still had her daily show on WOR Radio when I worked there, though of course Dorothy Kilgallen’s show with her husband, Dick Kollmar, “Breakfast with Dorothy & Dick,” had ended with her death in 1965. But reporting duties led me to encounter many of the guest panelists. The one who stands out was the actor Tony Randall, whom I interviewed one bright Saturday afternoon on the huge patio at Lincoln Center. He was dressed in a seersucker suit and wore a straw boater. Not many men could carry it off, but he could. He was one of the last vestiges of New York as I had imagined it.)

WQXR used to be “the radio stations of The New York Times,” and I was familiar with it long before I ever even visited New York. It was the home of the Saturday afternoon live broadcasts from the Metropolitan Opera. Opera doesn’t much appeal to me, but the commentary and the features between acts were fascinating. Coincidentally, Tony Randall was an opera expert and he would frequently be one of the commentators. (There’s a thread running through all of this, and it’s a golden thread.) WQXR was a 24-hours-a-day broadcast of dignified people playing dignified music and saying dignified things. (People I knew would come to work there: Kevin Gordon, just retired from the classical station in Philadelphia, and the great Sam Hall, who died in 2018. And I begin now to realize that my time in New York was as close to the days of the Algonquin Round Table as it is to now.)

Things changed. The New Yorker got sold and isn’t anything like it was in its best days. “What’s My Line” got canceled in 1967. WQXR got sold and while it is still on the air, everything is gone that made it WQXR.

Those facts make me sad, but what ought to make us all sad is that our modern world seems to have no place for the things that made them great. Little value is based on wit — and by this I mean true cleverness, not just being a smartass. There is nothing of the gentility that we saw as a goal even if we could not always achieve it. Politeness, manners, even basic decency as a starting point? All gone.

That’s true everywhere, but New York City is the poster child. Yes, the place always had its share of bad guys and there were always dangers in, say, walking the streets at night. But now it’s a full-time danger spot. Smoke from Canada came through last week. It was reported on. It was a distraction from the cloud of dope smoke that constantly envelops the city. Where once there were Rockefellers and Harrimans there are now the likes of Trump and Weiner. New York no longer even aspires to greatness.

New York was probably never as good as once (and, somewhere, still) I thought it was. To some small extent it’s probably not utterly as irredeemable as I think it is now.

We have our gadgets and conveniences, but we’ve abandoned the aspirations we might once have held. The things we might once have aspired to have disappeared.

I do not know how they could ever be restored, but maybe we can take a few minutes to remember them, and to mourn them.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation