Hot Air, Cool Helium

Maybe Amy Gibas is a visionary.

It’s been a few years since we spoke. The last time I saw her was during her oral presentation in support of her master’s degree in fine arts.

Her stated goal is “To investigate the human relationship to the astronomical universe and to reveal and strengthen the fragility of our connections to one another,” and on the website of an arts organization in her home town she exhorts fellow artists to “Always make the work you are passionate about.”

Many is the time I’ve cooked up a high-concept proposal to get an editor to let me do something I wanted to do anyway. I would not accuse Amy of this — she was, after all, awarded her degree — but something in me kind of hopes that her research proposal had something to do with a desire to have fun with balloons. About which she was nothing if not passionate.

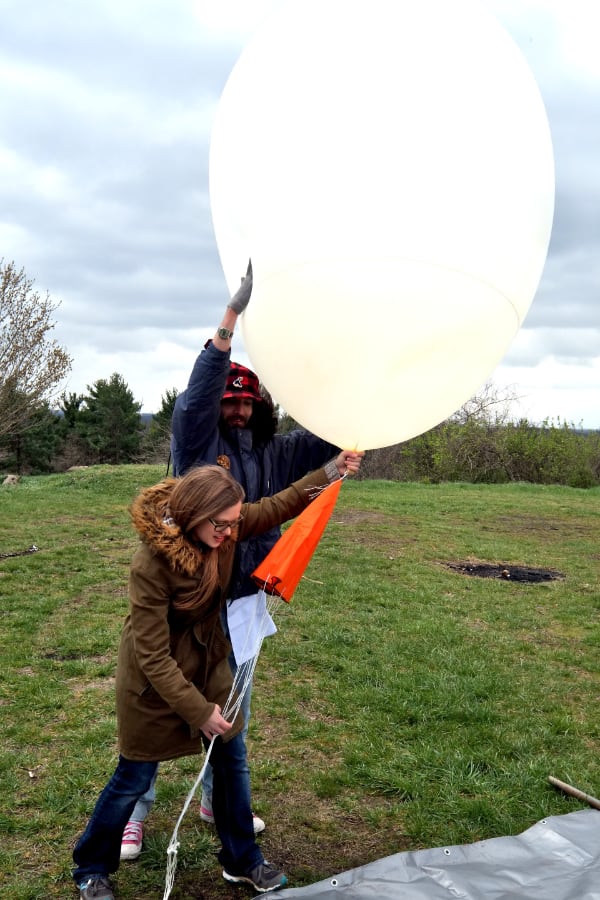

Amy came to my attention in early April 2016, when she was preparing for the launch of “Gibas II,” a lighter-than-air contraption she was using in research toward her degree. It was to be freed at the top of Radar Hill, and though the afternoon of April 9 was cold, windy, and gray, a half-dozen of her friends joined her for the event.

“Gibas II” (also Gibases I, III, and IV) were essentially weather balloons, but instead of the traditional radiosonde her payload each time was a wooden platform on which were mounted a GoPro video camera and a tracking device that was connected to the cellular system (where it was available). I believe there was also some kind of audible alarm that was to aid in recovery.

Details were carefully considered. A scale was used, upside down, to determine the amount of buoyancy provided by the balloon as Amy and her assistant, Dylan Berry, filled it with helium. Dylan had a slingshot in his right back pocket, for emergency use — what if they forgot to turn on the camera or, worse, the tracking gadget, and remembered only after it had been turned loose?

The idea was to make a film from the balloon, following its travels to wherever the meteorological muses carried it. This involved recovering it when it achieved an altitude where the air was so thin that the helium’s vapor pressure exceeded the now-much-bigger balloon’s ability to contain it. It would them pop (this was before Bugout Joe Biden had access to airplanes and very expensive munitions) and the payload would parachute to the ground. With luck, it would not land in a river or someplace inaccessible.

I suppose most people have seen weather balloons get launched; I used to see them regularly when I was a kid. (In those days, we’d also hear sonic booms regularly, before the development of oh-so-delicate sensitivities led to their prohibition.) But rarely has so much attention been paid to the release of one.

A picture of the launch made the cover of Monday’s newspaper; the headline was “To infinity and beyond” because the editor liked a children’s movie in which the phrase was used — and he repeated it in any story whose subject reached an altitude exceeding about one inch. (It’s a common malady. I had an editor at a very big paper who would manage to wedge in “the right stuff” anytime the modest airborne requirement was achieved.)

On that windy April Saturday the balloon and payload didn’t shoot into the sky, though its seemingly slow ascent was deceiving — before long it was so far away that if you hadn’t kept an eye on it you couldn’t see it anymore. It was carried by the prevailing northwesterly wind. The instrumentation worked, as witness the chart of its path (which also illustrates that most of that federal money for cellular coverage in rural areas seems to have gotten spent on something else). By late Sunday afternoon it had drifted a few hundred miles east southeast, into the West Virginia mountains. Then the signal stopped.

Amy and her crew headed out to find it, which given the terrain and sparse population was a long shot. Still, I got an email note from her that afternoon: “I know your deadline has passed, but I thought you might like to know that the Gibas II has been successfully recovered from Pocahontas Township West Virginia!”

(I think there’s a movie to be made about that launch and especially the search for it, because the circumstances involved display the kind of serendipity usually found only in movies.)

Gibas III, with much the same configuration, was released on November 5, late in the afternoon — it was hoped that some inspiring sunset pictures might have been obtained. There wasn’t much wind, and it meandered around locally and then . . . disappeared. Last I heard, there was no news as to its whereabouts. I keep hoping for the surprise email saying that it got found and returned to Amy, but so far that hasn’t happened.

The next June, Gibas IV got launched. Again, it toodled around locally and then, just as it was heading southeast, it stopped transmitting its location (or anything else). Late that night a West Virginia resident found it in the middle of a dirt road. There was contact information aboard, so Amy and her crew were able to retrieve it the next day.

All of which is a nice story of an enjoyable, sometimes tense, and imaginative (some would be less kind, but they’d be wrong) project. I think about it from time to time; just a few weeks ago, before the recent balloon/UFO menace, I dropped a note to Amy at her old university email address, pointing her to a YouTube balloon video that reminded me of her project.

It was quite a coincidence, in that just days later the Chinese balloon thing made its crossing of the U.S. and, after it had transmitted everything it was sent to get, it was shot down. The whole business surely did not inspire anyone’s confidence in the ability and resolve of the American military and government. Perhaps out of embarrassment, the president ordered the shooting down of two other aerial things, both small. We’ll never know what they were and I can’t help but think that the administration isn’t much interested in finding out what they were. (And I would not be surprised to learn that military contractors are descending on Pentagon procurement offices with ideas for a new shotgun-style missile capable of taking out an entire V of Canada geese with just one $1.6 million rocket.)

Ah, but back to the visionary status of Amy Gibas. The idea of private individuals and groups launching balloons for their own amusement and to gather data for their own use has become relatively common. Thus we have a headline from the February 16 edition of the authoritative Aviation Week and Space Technology: “Hobby Club’s Missing Balloon Feared Shot Down By USAF.” I did not make that up. Nor did I make up the name of the organization that thinks its balloon might have been one of those shot-down objects the government has decided not to look for anymore. It is the Northern Illinois Bottlecap Balloon Brigade. Really.

Their gadget is or was what is known as a “pico balloon.” There seem to be a lot of them floating around the world. They’re usually made of Mylar, the strong, silvery shiny plastic you’ve seen in the form of emergency blankets, which doesn’t expand and pop as high altitude is reached, the way Amy’s were meant to do and did. These balloons aren’t supposed to come down. They’re launched with the hope that they will fly around the world pretty much forever.

They are often equipped with radio equipment, and hobbyists worldwide have fun tracking them. The radios are powered by small solar panels. They’ve been known to more than circumnavigate — circumdrift? — the globe. According to AvWeek, they cost from just a few dollars to nearly $200, not counting the radio gear. (Or $14 million, if you’re the Pentagon.) They are very light weight and are exempt from airspace restrictions.

I especially loved this paragraph from Steve Trimble’s AvWeek story:

“I tried contacting our military and the FBI—-and just got the runaround—-to try to enlighten them on what a lot of these things probably are. And they’re going to look not too intelligent to be shooting them down,” says Ron Meadows, the founder of Scientific Balloon Solutions (SBS), a Silicon Valley company that makes purpose-built pico balloons for hobbyists, educators and scientists.

We oughtn’t make fun when people of diminished individual and collective capacity behave stupidly. But we might want to be alarmed when those people and organizations are running the most powerful country in the world.

Meanwhile, I imagine the Chinese military is looking into the use of tiny Mylar balloons, now that you’ll be seen as an idiot, and not without reason, if you shoot one down.

It is a mess.

The only conclusion I can make with any confidence is this: If you find the Gibas III, Amy Gibas would like to hear from you. I suspect she still wants it back.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation