Monday marked 144 years since Charles McGill was sent to learn (and begin) his eternal occupation.

It is said that he repented toward the end — and the record makes clear he had a lot of accounts to balance — though we cannot know whether he truly did regret events in a fully regrettable life. We can hope that he did and we can be grateful that it’s not our call to make.

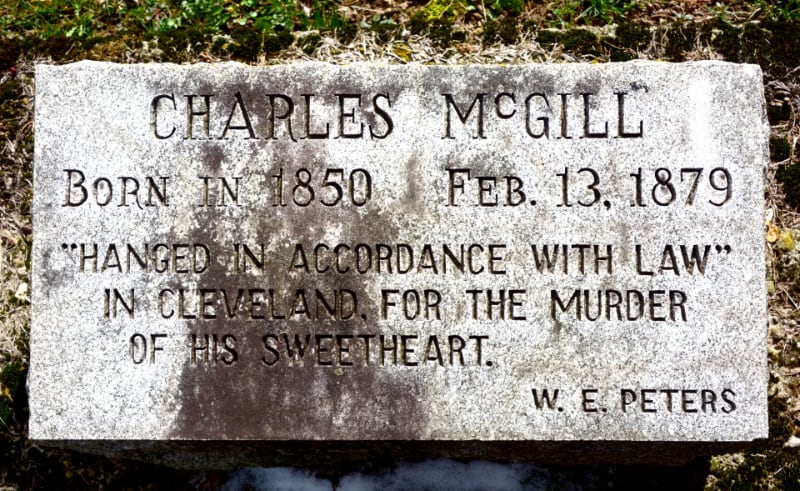

Charles McGill is of special interest to me only because five years ago, early for a photo assignment, I wandered through a local cemetery and found his tombstone. Shown here in a picture I made that afternoon, it raises questions, don’t you think?

I have great affection for the kind of people who wouldn’t just let it rest there. They would have to learn the answers to those questions. I have tendencies in that direction, too, though my laziness threshold is high and I’ll go looking only if the questions hold the potential of having really interesting answers. If they are likely to result in a story worth telling. Or, as in this case, two stories.

There’s a tremendous reward in learning local history. I say this as one who vigorously avoided learning any history of the area where I grew up, in central Missouri, an area known as “Little Dixie.” (The problem was worsened by the mother of a classmate of mine, who was a diminutive woman and happened to be named “Dixie,” so whenever the phrase I thought of her — still do — and thought she was getting too much attention.) Daniel Boone had come through the area, and it fought its own small version of the Civil War during the Civil War. One county to the east, Calloway County, declared itself independent of both the Union and the Confederacy and was henceforth known as the Kingdom of Calloway. (There’s even an exit on Interstate 70 at “Kingdom City.”) All fascinating stuff, but I never really considered myself as being “from” there — my mother was from Nebraska and my dad from Indiana, so its soil, no matter how historically fertile, was barren of my roots.

My family was big on genealogy, and three of my four major ancestral lines have been traced to this continent in the 1600s. (The fourth, my mother’s mother’s line, got here from Germany in the middle 1800s.) So there were places whose history interested us, but central Missouri wasn’t among them.

My allergy to local-but-not-my history was sporadic. When I lived in New York, its history caught my attention, just because it went back very far, though few of the old families survive — most people are fairly recent arrivals. In New England, the sense of history is strong, but you’re a newcomer if your family has been there for only 10 generations.

I cannot explain it, but I’ve been somewhat interested in the history of southeastern Ohio for the 18 years I’ve lived here. Part, I suppose, is because this place has always felt like home. Part is due to the Powell ancestors having gotten to their southern Indiana lands, surely, on the Ohio River, which borders the county where I live. Part is, I think, that I’ve never lived anyplace that has seemed so quintessentially American.

The Civil War was always a subject of family discussion, and a portrait of my great grandfather, Capt. Titus Cummings, hangs over my desk as I write this. He got shot at Chickamauga on his 33^rd^ birthday. He was expected to die but didn’t, which was good for me in that my grandmother was born in 1867. (A few years ago I had one of those animations done of the portrait; sadly, it made him look kind of shifty.)

Ohio lost a huge percentage of its population in the Civil War — something on the order of the generation of young men Great Britain lost in World War I — so I’ve felt an affinity for the place. The one Civil War battle of any note fought in Ohio, the Battle of Buffington Island, took place a few miles from my home.

This turned out to be an interesting place to me partly because at first it doesn’t seem interesting at all. We have an excellent historical society, staffed by people who are both passionate and knowledgeable, and who are willing to endure the peculiarities of some reporter-photographer guy who wanders in from time to time with the strangest questions.

Questions such as “Who was Charles McGill?”

When I asked the then-director of the historical society that question five years ago, he replied that he didn’t know, but he’d wondered about it, too. On the other hand, he could tell me all about W.E. Peters, the other question raised by that remarkable tombstone. Whom we’ll get to in a little bit.

I did research on and found out a bit about Charles McGill. I published it elsewhere a few years ago, and here’s what I wrote:

The first thing I learned about him, his enduring claim to fame, is that he was the last man legally hanged in Cleveland. During much of the 19th century, the gallows traveled from county to county, taking care of such business as needed its attention in each of them. In Cuyahoga County, it rendered its service nine times over the years. But after — though not because — Charles McGill was dispatched, the procedure changed, and the guests of honor were thereafter brought to a more centrally located place to be hanged.

For a while, that was all I was able to learn about the departed McGill. Then I happened upon “By the Neck Until Dead,” John Stark Bellamy II’s fascinating account of each of the court cases in Cleveland that climaxed at the end of a rope. And from its Chapter 9 (of course) I was able to learn about the man behind (or more accurately, beneath) the tombstone.

Charles McGill was one of nine children born to and raised by “a solid middle-class Athens County family.” His father is described as having been a cabinet-maker but Charles was loath to follow in the trade. Instead, he went to Ohio University. In Bellamy’s words, “The only education he acquired in his two-year stint there, however, was a precocious mastery in the consumption of alcohol and the pursuit of venery.” In which course of study he was probably not the first and certainly not the last.

In that he entered OU in 1864, it seems likely that the year of his birth on his tombstone is inaccurate, unless the school was accepting 14-year-old freshmen. In any case, he was out by 1866. He met and married Louisa Steelman, of Columbus, who in-between drunken beatings from him bore him two children.

The profession he chose, and for which he seemed well suited, was ne’er-do-well. In 1872 he abandoned his wife and children and took up with 19-year-old Mary Kelley who, it was said, “had a past.” Mary worked as a maid and at other jobs, one of which involved lingering suggestively at street corners. They moved in together, but there was friction. Though McGill seldom worked, he objected to at least one of Mary’s money-making pursuits.

The semi-happy couple moved around, first to Toledo in 1876, where Mary gave birth to a child (who was given up to adoption) and then to Cleveland. McGill continued to be a drunken lout, and Mary continued to earn money as she could. In due course, her patience ran out and she took lodgings at Laura Lane’s, an establishment catering to the interests of sporting gents, at 100 Cross St. (now East Ninth Street, south of Carnegie Avenue).

McGill visited her there the night of Dec. 1, 1877. He spent the night, much of which he devoted to an unsuccessful effort to persuade her to once again reside with him. The next morning as she slept he placed a cheap revolver he had purchased (by pawning a friend’s coat) to her head and fired.

“Go get a priest,” he claimed to remember her begging him. But he did not get a priest, instead giving her over to what she would have known as an unprovided death. He shot her 10 more times, stopping to reload. The police found him covered in her blood.

For the next little while, he confessed to anyone who would listen to him. He seemed proud of what he had done. He refused to change from the clothes soaked in Mary Kelley’s blood.

He may have been proud of his action but he was unenthusiastic about answering for it. At his trial he displayed what commentators described as a fairly convincing display of insanity. He also wrote poems to and about Mary, which found their way into the local papers. The jury was unconvinced. It was quick in finding him guilty, and the judge sentenced him to hang June 26, 1878.

But the unreliable McGill didn’t keep that appointment. Due to an irregularity in jury selection, he was granted a new trial. He didn’t feign insanity that time (or else he was enjoying a lucid period). The outcome was the same.

He embraced religion. And on Feb. 13, 1879, McGill was brought into “the bull pen” at the Cuyahoga County jail where waited 50 eager witnesses and a large mechanical structure involving a noose. McGill was polite and composed. He turned to Sheriff John Wilcox and said, “Now, don't you make any mistake about that rope.” Those were his last words and at 12:04 p.m. came an execution that The New York Times described as “the most humane, orderly and systematic of any ever conducted in Ohio.”

The Cleveland Leader the next day — Valentine’s Day — gave less a review of the quality of the work than a poetical description of the result. Its headline and first two subheads read:

THE GALLOWS

Again Does Its Fatal

Work

And Charles McGill Is

Launched Into

Eternity.

Which he, the mortal part of him, anyway, is spending in Athens’ West State Street Cemetery beneath that peculiar headstone.

So, one of the two questions posed by the tombstone of Charles McGill was now answered; the use of the word “sweetheart” may have assumed facts not in evidence, a phrase that would have been familiar to the subject of the other question, W.E. Peters.

I ended up writing about him, too, and see no need to do it again, nothing having changed, so here’s some of my piece from 2018:

William Edwards Isaac Peters was born in Ohio, though not Athens County, in 1857 to a family of apparently modest means. He became an engineer and moved to Athens to help prepare a section of land for railroad construction.

Before he was all done 95 years later, he had written a stack of books — not easy books, either — become a lawyer, been elected president of the Athens County Bar Association (though we must not hold these things against him; he made up for them in other ways), established the standard for measuring land in hilly places, and from all evidence walked every square foot of Athens County.

He first came to my attention a few months ago when I noticed a peculiar marker in the cemetery atop West State Street. It memorialized one Charles McGill, a man whose life was not well lived and whose life ended in a noose in Cleveland. In the lower right corner of the marker the name “W.E. Peters” was inscribed.

It was my good fortune less than an hour later to run into Tom O’Grady, of the Southeast Ohio History Center, astronomy, and numerous other pursuits, who was on Court Street talking to someone. Excited about the McGill grave, I impolitely broke in to their conversation and asked what Tom knew about Charles McGill.

Not a lot, he said, but he knew a great deal about W.E. Peters, and we should talk about him sometime.

The opportunity arose 10 days ago. It was in Tom’s office in the History Center. (Have you been there yet? If not, go there. If so, go there again.) I barged in, and Tom stopped what he was doing to give me the hour tour of the life of Peters. An hour was barely long enough to hit the high points.

“His history of Athens was published when he was 90, and it is labeled ‘Volume I,’” O’Grady said. “Talk about an optimist!”

Peters had worked as an engineer here and came to have extensive knowledge of surveying and the land in general. He became a lawyer specializing in land dealings. In due course, he came up with a method of measuring uneven land and published a book on the topic that was internationally seen as the standard work in the field.

He published a detailed history of land in Ohio, illustrated with finely done maps he had drawn himself.

“He walked every cemetery in Athens County and nearby parts of other counties,” said Tom. In fact, based on the maps he published in later books, he walked every bit of Athens County. The detail would put Google Earth — the photographic version — to shame. Every gully is illustrated. Every abandoned church or school — and there were a lot of them — is shown. There are notations such as “Cemetery, one grave.”

There is no evidence that Peters was especially fascinated by cemeteries, and by that I mean he seemed no more interested in them than he was everything else in the land around him. Yet he made a mark in the area’s burial grounds. The marker for Charles McGill wasn’t unique, by any stretch.

“He would put markers where he thought they were needed,” said Tom. “They have inscriptions about the person. There’s one for a Confederate deserter that mentions that he was killed by a Confederate officer sent north for that purpose.” Another memorializes the burial spot of a runaway slave, about whom nothing else, not even his name, was known.

Peters died in 1952 and is buried in the West Union Street Cemetery.

He had his law office on Court Street and lived in the house that was later converted to various businesses, the most recent being Buffalo Wild Wings (you can still make out the roof line). He was married, though he and his wife had no children.

O’Grady talks of how Peters had somehow come to know a family living in the county in very penurious circumstances, and how he took them fuel for their stove in the winter.

“I think he was taking them his unsold books, which they burned to keep warm,” he said. “That might explain why his books are so hard to find.”

Peters and his wife established a library here. There is a section of the law library on the fourth floor of the Athens County Courthouse that was donated by him. His papers, well, many of them, are in the Archives & Special Collections section of OU’s Alden Library, while even more of them are in Columbus.

Such a person, you might suppose, lived in grand style and died a rich and respected man. You could be forgiven for the guess, but you would be wrong.

Peters came into a dispute with some of the county’s leading lawyers — it may have arisen from efforts, which right or wrong were successful, to have the court appoint a guardian to watch over him in his final years — and he died, poor, living in a modest house across the street from the post office in The Plains, his law office being in the garage.

Interesting tales, no? I hope you found them interesting, anyway. Because my point has little to do with a fellow who went from dissolution to murder, nor an enterprising and fascinating engineer-lawyer-surveyor. Instead, it has to do with my entirely unintentionally having been early to an appointment, passed the time by strolling through a cemetery, discovering a puzzling tombstone, and not being satisfied. More than that, by the fascinating results that can accrue when historical curiosity leads to a little research.

It’s in service of a lesson. If you look around, you’re likely to find something that is historically significant, not in the history-book way or the doctoral-dissertation-subject way, but as some fascinating glimpse of history that isn’t widely known. It’s well worth the effort.

As it was when in the fall of 2020 I learned there would be a little ceremony in the river bottom of an adjoining county, a couple miles downriver, as it happened, from Bluffington Island. It turned out that exactly 250 years earlier, on the night of October 28, 1770, a young surveyor who was doing work for the Ohio Company in which his brother was an investor, had camped out there. There’s a marker there and everything, though it’s out of the way and few knew about it.

The surveyor would later become famous for other activities. His name was George Washington.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation