What a Young Soldier, Uncle Sam and a Swiss Theologian Can Teach About Power

Earlier today, I found myself reading an article on Bradley Manning, a soldier in the U.S. army who is suspected of being the source of the material that WikiLeaks has been disseminating. Since his arrest, the private has been placed in solitary confinement without any crimes charged against him – a seemingly arbitrary decision enabled by the army’s virtually absolute power over him. As we contemplate situations like this, supporters of such policies would likely argue that granting the government such near absolute power to hold people without charges is permissible because it is for the greater good. Opponents might say only God ought to have absolute power. Maybe God doesn’t want such power, either.

The power factor keeps coming into play in current debates. Should the government have the power to force people to obtain healthcare? Should the government be able to force people to be blasted with x-rays if they wish to travel? Should the government be able to perform warrantless wiretaps on our conversations? Each of these matters revolves around whether Uncle Sam should be allowed to increasingly move towards absolute power, less and less bounded by existing rules.

As I mulled over Private Manning’s situation, I thought back to a particular theological subject I had been reading on a few weeks ago: God’s absolute power or lack thereof. It is not everyday that one can take a political hot topic and connect it to a major theological subject, but this so happens to be a time when theologians pondering God also end up giving us something to chew on in our political policymaking.

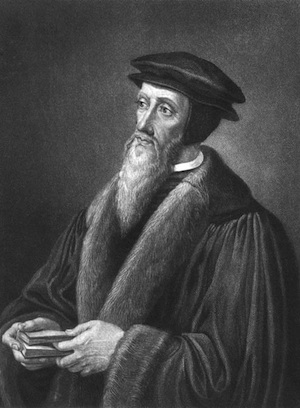

The famed Genevan Reformer John Calvin’s wrote on the matter of absolute power in his magnum opus, the Institutes of the Christian Religion. His concern, of course, was God and not the state, but his observations are apropos. Calvin writes, “And we do not advocate the fiction of absolute might; because this is profane, it ought rightly to be hateful to us. We fancy no lawless god who is a law unto himself.” Sometimes it might seem preferable that God did have such a completely arbitrary power that he could even contradict himself if need be for the greater good.

Nevertheless, the famed theologian rejects absolute power on the part of God because then he would be a “law unto himself.” Normally, people speak of God as a being who can do whatever he wants whenever he wants it. But, what Calvin recognized is that such a description would draw the picture of a capricious being not consistent with the Biblical view of the deity. Instead, the Christian tradition has insisted, God is bound by his own holy nature to do what is good. His power lacks the power to contradict his own nature, in other words.

The Bible time and again agrees.

If God himself is not an example of “absolute might,” why is it that in our own human planning, we so often willingly build a system where the collective entity known as the Government is given as close to absolute power as possible? Yes, in the United States we have a constitution that restricts power, but increasingly we show a tendency to let that constitution be ignored or manipulated whenever the clear intent of it opposes what we want or what we think will grant us the greatest “safety” (a nebulous and dangerous to pursue object when not tied to other principles).

Whether one agrees with the various examples of increasing governmental power mentioned above or not, the real question we must consider is what the metric is that we use to determine acceptable thresholds of power. If a pious theologian could recognize that for God to be good not even he could be said to have “absolute might,” how much more so ought we to recognize such about our governmental authorities?

Timothy R. Butler is Editor-in-Chief of Open for Business.