A World of Definitional Gerrymandering

We need to define terms. Our culture is always ready to debate and toss accusations, but we fail to stop and see if we even mean the same things by the words we hurl. No wonder we never settled anything.

A recent exchange I found myself in with a reasonably well-known theologian reminded me of this problem. The discussion started with a public post he made, trying to assert his corner of the church world had protective distinctives that had shielded it from a particular set of increasingly discredited, abusive leaders.

Trouble is, his corner was the one I lived in for a decade and a half and still neighbor. I knew his claim contradicted the reality I had witnessed.

At issue was the movement that emerged about twenty years ago. An informal group of then relatively young theologians, all friendly with each other despite different church backgrounds, took the world by storm. A Christianity Today column and subsequent, eponymous book on the “Young, Restless and Reformed” by Colin Hansen put name to the movement. Even Time took note, referring to “the New Calvinism” (another name courtesy of Hansen) one of 2009’s “10 Ideas Changing the World Right Now.”

Now, I’ve benefitted over the years from some in that movement, so I would be disingenuous to throw the whole thing under the bus. But, figures like CJ Mahaney and Mark Driscoll creeped me out even in the movement’s early going and their authoritarian, sycophantic and narcissistic leadership style was later revealed for all to see as people shared abuses they experienced under them.

Unfortunately, their disgracing came after influencing a whole group of those entering ministry in the 2000’s and 2010’s. I’ve borne witness to the wreckage Driscoll-wannabes have inflicted over the years. They weren’t in some far-flung part of the church; they were squarely located in the denomination the gentleman I was disagreeing with claimed was immune to such.

How could a well-respected thinker and theologian say a movement simply didn’t exist in his theological circle when I’d personally witnessed them there?

Thus began the discussion. At each point of the back and forth over the course of a day, I asked a simple question: “How are you defining ‘Young, Restless and Reformed’?”

Admittedly, the movement is somewhat informal and nebulous. Pinning it down is hard, but the family resemblance is there amongst all the New Calvinists, no matter their denomination.

They all take a meaty Reformed theology of God’s sovereignty and grace, along with some favorite historical proponents such as Jonathan Edwards, as a way to engage contemporaries with both cultural and technological savvy. Figures such as Tim Keller, John Piper and Mark Driscoll all share that distinct family resemblance despite their vastly different temperaments.

First, my acquaintance claimed I misunderstood when I suggested a relatively calm, broadly accepted figure such as Piper, a decades-long Evangelical “thought leader,” was part of the movement. The simplest way to distance a movement — as he wanted to do — is to say, “No, it’s those people, not anyone I agree with or respect.” I then provided a link to a transcript of a speech given by Piper in which he explicitly said he was a part of the movement and sought to define it.

I get why he wanted to avoid including Piper: he regularly asserts conservative Presbyterianism is immune from such movements and their abuses. If a pastor and theologian like Piper, tightly associated with many of the best and brightest Presbyterians, was also part of the movement, it puts the lie to the claim.

Unable to deny Piper’s own words, my acquaintance redirected: “It’s a Baptist movement.” While he and Piper would agree on an awful lot, Piper is Baptist and he is not.

At each turn of this theological discussion, it moved much like I’ve found political discussions go. The subject is kept poorly defined and moves to fit a person’s desired outcome: he and his are not part of the bad thing, whatever it may be.

If a Presbyterian wants to avoid having a movement associated with his own denomination, the easiest way is to define the movement as all the things it is plus Baptist. This, though, is circular logic.

A Presbyterian can’t pat himself on the back for his denomination avoiding a movement’s influence by conveniently defining the movement as Baptist. Nor does it make sense when well-known Presbyterians are clearly contributing to and even taking part in leadership of the movement.

Hansen, years after giving name to the movement, reflected that it showcased “cooperation between churches,” specifically referencing “Baptists, Presbyterians, and charismatics.” To his point, he highlighted Presbyterians Keller and Kevin DeYoung alongside the notable Baptist examples. He did so standing on the stage of one of the many conferences of the 2000s and 2010s where the denominationally diverse New Calvinists constantly collaborated on shared theological convictions.

Of course, Presbyterians, who baptize babies, aren’t Baptists. But, if you look at the movement’s ideology, baptism’s only big hook in it is that, as Piper noted, it was a Reformed movement that didn’t exclude Baptists.

If you were speeding in your gray car, you can’t claim you weren’t by defining speeding as going over the speed limit in a brightly colored car. If the only reason an undesirable group isn’t in your circle is that you’ve made “it isn’t part of my circle” part of the definition, your claim is meaningless.

Moving definitions are a pervasive problem, not merely a bug present in idiosyncratic debates between theological nerds. Politicians and their proponents constantly flood us with unnecessarily destructive arguments made so because no one bothers to define and stick to what words and phrases mean.

We’re all vulnerable to this.

Consider the Ferguson Protests of 2014 and the events of January 6, 2021 in Washington, D.C. Almost everyone will insist one of those was out of control and destructive, but nearly as many will claim one was “mostly peaceful.” They just won’t agree on which one.

As you read the last paragraph, you probably knew your answer to which is which, even if you know your (ill-informed) neighbor would pick differently. How can that be?

To those favorable to a given protest’s goal, the situation is always “mostly peaceful,” because anyone who wasn’t peaceful is explained away as an interloper not really a part of the “movement.” But, when the shoe is on the other foot and the “movement” is across the ideological spectrum from one’s viewpoint, every destructive thing is eagerly attributed to the whole mass protesting.

That’s why it is crucial we define terms. If we agree to a standard of what is peaceful and what isn’t and who is within a movement and who isn’t, we can’t conveniently place the troublemakers outside our ideological borders just because we want to.

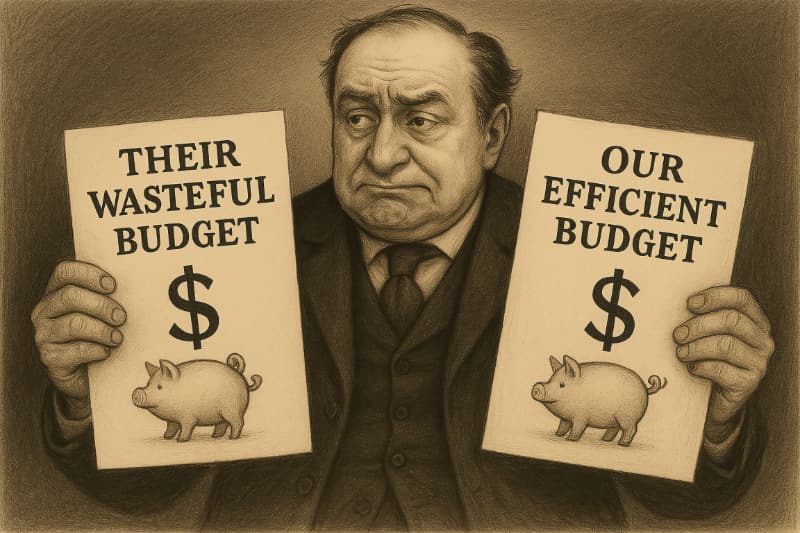

The same applies to ideas, not just people. President Trump’s and Elon Musk’s explosive debate last week is a case in point. An old pearl of wisdom from witty political observers says a new spending bill is “necessary spending for the prosperity and growth of our country” if you are the party in power. Conversely, it is “unchecked spending promising to bankrupt us” if you’re the minority party.

Often, the same politicians will make both arguments as the balance of power shifts to or from their party. Sometimes, they attack proposals to spend precisely the same amount they defended months before. The key is their glaringly obvious definition of “wasteful spending” they’d never admit: “wasteful spending is spending proposed by the other guys.” This definition is blatantly unhelpful, as the deficit keeps increasing regardless of who is in charge, but it serves to defend the quality of one’s own party.

Politicians can never resist gerrymandering. Sometimes, the literal sort, distorting the borders of voting districts to the point of absurdity to gain more favorable elections. Other times, it is distorting terminology for the same reason.

So it goes whether dealing with the Young, Restless and Reformed or a sprawling budget. We all face that temptation to gerrymander to preserve the sheen of our movements and our viewpoints. No one eagerly includes the worst elements, even if by any reasonable definition, they are unavoidably a part.

When we distort the borders to protect our turf, we harm our own ability to improve. If we define our affiliations, be they “Young, Restless and Reformed” or “Conservative” or “Liberal” or “Swiftie” or whatever, in a way an outsider would say, “Yeah, that sounds right,” it forces us to face both the good and the bad.

Defining terms carefully, even ones that box us into ugly truths, encourages us to face our flaws, rather than define them as someone else’s problem. We correct by being more introspective to where our own ideological, theological and political schools may lay the toxic seeds of the Bad Guy we can no longer conveniently — but arbitrarily — disown. Faced with our dirty laundry, perhaps we also grow more charitable to others, rather than always being ready to tar them with their worst parts.

A few years ago, I officially resigned from the denomination I originally served in as a pastor in part because of some of those worst elements. The ones my debate partner claimed weren’t there at all. My personal convictions have stayed much the same and I still minister much the same, though, so I can’t just wash my hands of those excesses as “someone else’s problem.”

No, I remain indebted to and still appreciate figures within the Young, Restless and Reformed movement. Tim Keller left a deep impression on me and the movement’s New City Catechism has been a tool I regularly minister with. Well defined terms just prevent me from conveniently removing the Driscolls and Mahaneys from a theological movement I was enriched by.

Being forced to face that dirty laundry allows us to do something important: to realize the problems are there and thus we ought to be discerning and humble. Across political and church spheres, if we had to face the ugliest parts of our own realms, because we carefully, rather than conveniently, define our terms, we would know what to guard against.

To non-philosophers, someone saying, “Let’s define our terms!” can sound obnoxiously pedantic. Perhaps, sometimes, it even is. But, by and large, we need to do so more often, not less.

Philosophers make that cry because philosophy is about thinking clearly. Clarity helps us improve our own camps and bless others, rather than just hunkering down for the next war.

Timothy R. Butler is Editor-in-Chief of Open for Business. He also serves as a pastor at Little Hills Church and FaithTree Christian Fellowship.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation