Sometimes the Least Bad is the Best

My good friend and fellow OFB writer Dennis E. Powell and I met years ago on a group that championed Free/Open Source software, much for the same sorts of reasons he advocates for his new phone configuration over Apple’s offerings. OFB itself was founded, in fact, to promote such open software, especially Linux, so why would I defend locked down systems from Apple? That’s a story that started 19 years ago, before the iPhone even existed.

My take on phone platforms and my advocacy for #TeamApple is closely related to that time I spent as an avid Free Software advocate. I had been experimenting with the Linux desktop in the late 90’s while still running primarily on Windows, but after several bouts with viruses and multiple reinstalls of Microsoft’s most robust operating system of the time, Windows 2000, I was done. For about four years, I did almost everything in Linux. Open for Business’s name even derives from its original mission to be a guide to adopting such Free Software solutions.

This is a part of a two part point-counterpoint series on privacy in mobile systems. You can read Dennis E. Powell’s take here.

While upgrading to the latest Linux was often a multiday process of coaxing software and hardware to work again (longer if moving to a new computer with new compatibility issues), when it was running, it looked good, ran stably, performed quickly and had the bonus of being “free” — not under the thumb of the corporate behemoth of Redmond.

Each year in the late 90’s and early 2000’s were hailed to yield the Holy Grail, “year of the Linux desktop,” the year that this upstart operating system would finally reach normal users (e.g. not those of us already using it). With Apple seemingly relegated to the also ran of brightly colored computers, Linux was what would stop Bill Gates’s giant from controlling absolutely everything.

The “Linux for the masses” goal was always tantalizingly close but just as out-of-reach. I jumped from the K Desktop Environment (KDE), favored by Linux flavors such as SuSE, to GNOME, favored by RedHat, when the latter seemed to get closer to the goal, but it still wasn’t there. And I was reminded of that every time my display adapter got messed up or a software upgrade broke all the menus.

Or, fatefully for me, in 2004, when my computer forgot how to print. Rushing towards final exams and papers in college, I went to print an assignment and the printing subsystem died for the second or third time in as many months. With no time for a deep dive into configuration files and logs, I looked over at the PowerMac G5 I had purchased — ironically, to run a specialized version of Linux on — thought about how Apple’s still relatively new Mac OS X was working just fine on it and switched over to it to finish the academic term.

I never went back.

While Windows was buggy and insecure, Mac OS X did what I’d always wanted my Linux systems to do: provide me with a stable, robust computer that supported open standards and resisted the constant barrage of security threats on the Internet. It wasn’t fully open and there were a few frustrations here and there, but it bested my long advocated for Linux desktop in one key way: it just worked.

Many others who were early advocates of the Linux desktop also jumped at roughly the same time. The Mac had gained a fresh operating system that was a cousin to Linux; while not entirely open, it favored open standards instead of Microsoft’s proprietary ones, had many of the same powerful tools as Linux and yet bested Windows for ease of use.

Ironically, it was under the often-evil auspices of Google, the last decade’s replacement villain for the 1990’s Microsoft, that did manage to popularize the Linux desktop in the form of Chromebooks. That, however, was years later and is another story. In the mid 2000’s I set aside my dreams of helping all my friends, family and IT clients join the Linux revolution and started recommending the Mac. It helped those get all of them away from buggy, insecure Windows PCs while also being easy enough to use that average people could successfully make the switch.

Taking something good but inaccessible for most and making it accessible for nearly everyone has consistently been Apple’s specialty. Much in the same way as I described above, the iPhone’s arrival hailed the moment the full Internet became something normal people could access from a “smartphone” (quibbles aside about whether the iPhone was a “smartphone” when it first came out).

Vastly easier to use than SymbianOS smartphones like mine or the leading options from Microsoft or Blackberry, it defined the modern smartphone, whether it is an iPhone or Android.

The first iPhone demanded certain compromises from users —- they had limited Bluetooth, slow connectivity, no copy and paste and no third-party apps at all. Yet, the compromises paled compared to what it delivered: the real, unwatered down Internet in one’s pocket unlike any device of the time. Windows Phone, QPE, PalmOS, SymbianOS, BlackBerry —- they all checked off more boxes of features, but for most users, the iPhone was better because you wanted to use it.

This is all ancient history, but I would suggest that what Apple did in adding back real alternatives to Windows and creating the modern smartphone speak to what Apple offers on the privacy front Dennis addresses. While philosophically, I’d prefer the openness of a Free Software phone stack like he is using, few users will be brave enough to buy a new phone and immediately start flashing different bits of software off the Internet onto it to create a secure phone.

Apple offers a “good enough” alternative here as it has before, vastly better than what most users will use otherwise (a standard Android phone).

Is it really “good enough” when it comes to privacy? Dennis points to a class action lawsuit against Apple for privacy invasions, but that suit appears to be questionable at best. The tracking Apple is accused of is on its App Store and a few other built-in apps and the data Apple is accused of transmitting matches what most people would expect it to. For example, when you browse the App Store, it only shows you software compatible with your device. Is anyone really surprised, much less upset, that the App Store transmits what model iPhone you are using to Apple as part of the process of displaying those catered results?

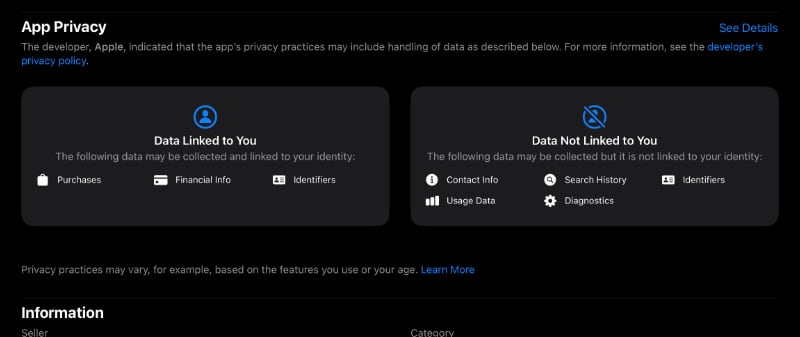

What’s more, Apple is upfront about it. The company has been the pioneer of publishing “privacy nutrition labels” in its App Store, requiring developers to list how they use our data. Apple itself publishes those labels for apps such as those in the suit and explicitly details in an easy-to-read table what data it collects. This is not the sinister sort of hidden tracking companies like Google and Facebook try to do against you every single day.

Meanwhile, Apple has been combating the very sorts of more sinister data usage Dennis describes. He describes installing layers of protection on his modified Android device to prevent Google from acting like, well, Google acts. Facebook and friends have viciously attacked Apple because, unlike Google, it exposes and prevents this sort of Orwellian tracking.

On the web, Apple has long been on the leading edge (pun not intended) of browser makers for fighting tracking cookies and other such insidious machinations. The Open Source browser darling, Firefox, has also fought the good fight, but Apple has the market size Firefox does not and it has welded it to good effect.

Is it perfect Perfect? No, and there’s reason to worry about Apple and its in-App Store tracking as even those of us who most love Apple find it getting a little too enamored with in-store advertising for our comfort. But I think we’d all agree there’s a difference between being tracked by the in-store security cameras while shopping Target and if Target attaching a tracking beacon to our cars while we shopped and followed us home.

Google and the other big tech companies do the latter; based on all the information we have, it appears Apple —- at worst —- is essentially doing the former. Bad? Maybe. Comparable to the others? Not at all.

Granted, building one’s own custom Android stack is even more secure. My early Linux desktop had security and openness advantages over the Mac OS X of the time, too. Nonetheless, the compromises — complexity, constant tweaking, difficulty when it came time to upgrade to a new device — mean few have the technical knowhow to feel comfortable doing it and even fewer have the willingness and time.

Apple’s closed approach isn’t ideal, but I would argue it is as Aristotle reflected on democracy: the least bad option. When companies and schools insist on hopelessly insecure software like Zoom, at least running it on iOS or iPadOS means that such negligent, if not willfully malicious, developers must remain in Apple’s security sandbox where they can’t spy on you when they are closed or hurt your other apps. In a system where the privacy rules can be dropped, like Android, companies can simply demand you drop those rules. If your workplace says you must use some invasive product, and your phone’s platform doesn’t enforce privacy protections, what can you do? You suck it up and get spied on.

Apple iOS is a firewall against that.

![]()

Apple has stood firm for privacy in most cases, even against enormous government pressure. (Most cases not being all, sadly.) The company brought end-to-end encryption to the average user, for example. When you write an iMessage (a “blue bubble”) to someone, neither Apple nor the government have the means to read it. Such technology existed before and is more readily present now in apps like Signal, but Apple once again has brought what was in the reach of only the technorati and made it mainstream.

Apple has also been a force for good on privacy in the cloud services we increasingly depend on. For example, when you ask your phone for driving directions, a great deal of information almost unavoidably must be given to some provider — be it Google or Apple or someone else. Those mapping providers, who generate data such as the traffic reports that help route driving directions, by gathering a worrisome amount of our location information. Apple has led the way on intentionally corrupting —- yes, corrupting —- that data sent from iPhones, through a process called differential privacy, to provide reliable directions while also protecting privacy.

Dennis notes that his phone’s Google camera app cannot even do simple tasks like keeping photos properly oriented to how they were taken without phoning home. His security system prevents the phoning home, but also breaks the orientation correction. Is that a deal breaker? No, but I like that on my iPhone I do not have to choose between my camera app phoning home or being partially broken to get photography that can best my DSLR frequently.

The revolution of Machine Learning drives this point further. So called AI has brought about nifty features such as facial recognition in photos and, even more amazingly, the ability to search for, say, “cardinals” and have one’s photo library return pictures of redbirds. Nowadays, photos can even be searched for text within them. Google, Facebook and their compatriots offer these gee-whiz features by taking more and more of our data and compiling it on their high powered, centralized computers.

(They don’t centralize all that data about us purely out of selfless service to us.)

On the other hand, Apple has gone the arduous path of developing the unquestionably fastest processors for its mobile devices to do those same tasks without sending the data off your phone, tablet or computer. Sometimes Google’s machine learning is smoother, but Apple strikes a balance: the convenience of the new features but with much greater privacy.

One can live without machine learning, though in another piece in the near future I’m going to explore more of why I think that’s not a long-term solution. One can even live without conveniences like driving directions or app stores or ever putting any meaningful information online. Here’s the simple truth though: most of us won’t go that route.

My Linux desktop at the height of my advocacy for it was perfectly capable of the basics in an affordable, highly secure form. It just demanded too many concessions for everyone I tried to share the setup with and, ultimately, even for me.

End-to-end encrypted messaging has existed for decades, the task of making it work was just too much for most people to ever bother with it. Preventing the sort of tracking Apple has cracked down on could be done without their help, but a whole lot more people benefit from that help.

Making good enough security and privacy accessible to virtually everyone is a big deal. I agree with most of Dennis’s criticisms, so I’ll concede again that Apple is less than perfect. But it achieves nearly what Dennis’s setup does and it does so right out of the box, with zero technical expertise needed. The iPhone SE priced in the same neighborhood as Dennis’s Google Pixel 6a has all of Apple’s privacy protecting software I’ve described above and its processor will also massively outperform what a Google Pixel (or literally any Android) can do in local processing power, the secret sauce to the next generation of privacy-protective machine learning measures I described above.

The trend is in the right direction, too. This year, Apple will complete its end-to-end encryption journey, taking the few remaining components of its cloud services that were not so and bringing them into that secure realm shut off from the government’s, malicious actors’ and even Apple’s attempts to watch us.

Thus far, the only breaks I’m aware of in Apple’s security on its cloud services have been through social engineering phishing scams: people getting tricked into giving out their authentication information. We ought not blame ADT if we give burglars our house keys and the alarm system code. Neither should we blame Apple (or any other tech company) for security breaches that are the digital equivalent thereof.

Even if Apple does offer a “good enough” option, I am glad the alternative Dennis describes exists. His setup is cool and, more than that, I would not trust an Apple that lacked legitimate competition —- quality alternatives keep a person or company honest. And, for some, the compromises of a rebuilt Android may indeed be worth it for even nearer to perfect privacy.

Yet compromises exist regardless of platforms and a good junction between privacy, control and ease of use is “least bad option” for most users. Maybe Aristotle would have been an Apple user.

Timothy R. Butler is Editor-in-Chief of Open for Business. He also serves as a pastor at Little Hills Church and FaithTree Christian Fellowship.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation