Every muscle was tight and trembling, like a thoroughbred in the starting gate, steaming and snorting and eager to unleash its immense pent-up power.

But it wasn’t a horse. It wasn’t an animal at all. It was the mighty IBM Selectric typewriter, and anyone who has ever used one knows what I’m talking about. Turn it on and it made a sound, a deep, motor sound, as if it were waiting to lash out at potential prey. Touch it and it wasn’t exactly vibrating, more making a tiny, powerful, circular motion, like a heavy flywheel deep in its terrible bowels was ready to send a fragment of harmless paper into another dimension.

The Selectric imparted a sense of power. Anything written on a Selectric was to be taken seriously. What it had to say could not be mistaken or confused, especially if you were using a font like Bookface Academic72, which was 10 pitch. The Selectric measured type size by pitch, characters per inch, so 10 was bigger than 12. The Selectric had balls, which IBM (and no one else) called “elements,” and by that I mean the strange golfball-sized silver things you could clip onto it, that spun at light speed with the right letter coming into place just as the ball, with its megaton force, slammed into the paper. You almost felt as if you should be wearing protective clothing, except in those days no one ever wore protective clothing. No fine watch demonstrates better mechanical precision.

It was my good fortune to have grown up in a newspaper newsroom, years before the Selectric came to be. It was a place of tall wire wastebaskets, over-full ashtrays, spilled coffee, Dixon Extra Black copy pencils, and a great deal of noise even when the press wasn’t running: the teletype machines and the wirephoto machine lined the back wall, next to the KFRU Radio newsroom. The wire machines were all the time clacking out copy, punctuated as events required by bells whose number corresponded to the urgency of the item being reported, from the many dings of a “flash” through the five bells of the “bulletin,” and the three of “urgent.”

(In later years these could be really irritating: in the 1980s, FBI Director William Webster was fond of making evening speeches, which were always covered by the Associated Press, which in turn would move its story the middle of the night. And the bulletin bells — they were now actually beeps, but were called “bells” anyway — would go off. We would look, there in the radio network newsroom in New York, for the bulletin, and there never was one. Why, then, the alarm? Because Webster’s name included the magic letters “EBS,” the signifier of the Emergency Broadcast system, and an EBS message was an automatic bulletin. I have digressed but do not apologize for it.)

Take the old newspaper newsroom wire machines as background noise. Add to it the constant sound of phones ringing, the frequent shout from the switchboard operator across the room to “pick up your phone, dammit!” or the city desk hollering to the switchboard operator to switch a call to a particular reporter.

Then, atop it all, mix in the sound of a dozen manual typewriters, no two the same kind or age or sound, at which reporters were clacking out stories on paper cut from the end rolls of newsprint from the pressroom. Because no one seemed to know how to replace a typewriter ribbon or knew where to find a new one, as the ribbons got worn out and the typing fainter the pounding on the keys had to become harder. And louder.

So I was raised in the belief that typing was a loud enterprise if it was to be at all important. Certainly if it was to be satisfying.

When the Selectric came along 15 years later, it was good and loud. At a radio network I once taped a minute of a Selectric typing. By speeding it up and slowing it down and adding just a pinch of reverb, and mixing the tapes one atop another, I produced a very convincing soundtrack of an epic battle, with machine guns, cannon, rifles, and explosions. (Slow news day.)

All things must pass. Noisy newspaper newsrooms are gone. Manual typewriters are the stuff of thrift shops. The IBM Selectric typewriter is now mostly gone — not counting the half dozen of them I have squirreled away upstairs — though I think if you ordered enough of them IBM would crank up the machinery once again. (Given IBM’s recent fortunes, I think they would probably come round and wash your car, for money.)

So by the time computers arrived, people who wrote things worth reading had a pretty good idea what typing was supposed to sound like. To IBM, it was the sound (and feel) of typing on a Selectric. IBM deliberately made its keyboard, the unsurpassed Model M in its many sizes and shapes, feel and sound like a Selectric keyboard.

Other companies had a different idea. The most famous of these, Compaq, made a keyboard that was as close to silent as possible. If you want to know how that worked out, hop down to the computer store and buy a bright new Compaq. Oh wait, you can’t.

This was a time of keyboard wars, and keyboards were a nontrivial purchase. At the top of the heap was the Northgate Omnikey, which was shipped with Northgate computers. Northgate soon discovered it was selling more keyboards than it was computers, and it continued selling keyboards long after it had ceased selling computers entirely. I have a couple and would be using them still but for the two spacebar springs on each taking a set such that one space would come out as two spaces. I’ll need to pop in to Springs-r-Us someday and get replacements.

Unlike my friend Tim Butler, who is fickle, maybe promiscuous, about these things, hopping from keyboard to keyboard and never giving it a second thought, I’m very serious in choosing a keyboard, thinking of it as a trusted writing partner, a companion faithfully delivering my words to the screen before me (and now before you). I do not think I’ve used more than a dozen keyboards regularly in my life. After the Northgates came a trusty IBM Model M, second edition, of which I have several. (I also have a very early one, made in 1986, that is too valuable to use unless I am acclaimed president, whereupon I’ll use it for my inaugural address.) They are the Colt Government Model of keyboards: not perfect, but reliable, predictable, and lovable once you get used to them.

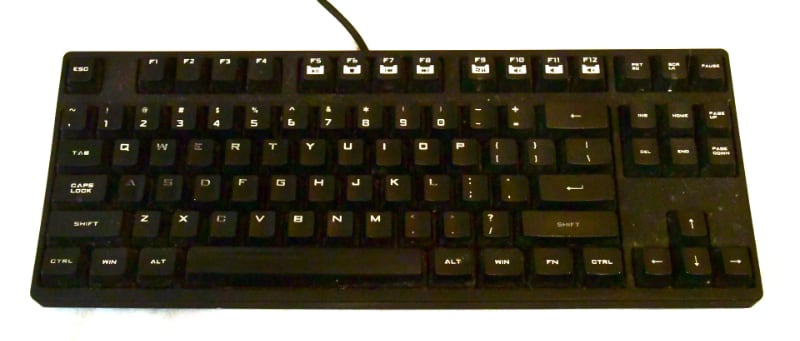

Also, the letters don’t wear off the key caps of a Model M, the way they do on other keyboards. It’s funny how keyboards show wear. New ones always feel strange to me for a few months, until the spacebar’s matte finish is worn shiny where my thumb or, I notice now, my index finger hits it. Also, based on the cheap paint that’s rubbing off of the 10-year old Cooler Master Storm QuickFire Rapid Tenkeyless Mechanical Gaming keyboard I’m writing this with, I use the A, S, E, and D keys more than any others, or else that finger is especially abrasive. (No, I do not touch type, though I plan to get to it right after I achieve fluency in Japanese.) Model M lettering doesn’t fade.

I got the Cooler Master Storm when I heard that it was very loud. It is, too. The IBM Model M keyboard sounds much like a Selectric keyboard when the typewriter is turned off. The satisfying sound of the typewriter came from the ball clacking on the paper. (In the early days, I actually sought a program that would emulate that sound on my computer. I did not find one.) The Storm doesn’t sound like a Selectric. It sounds like a manual typewriter, growing louder as the keys are hit with increasing authority. So I kind of love it. I got two, which is good because they’re long discontinued.

In the 1980s, everything was advertised as “turbo,” which had a vague, usually misused meaning intended to send the message that whatever this was — toaster, toilet, turntable — was faster than one without turbo. Today, it’s “gaming.” Means the same thing as turbo — nothing — but you’re supposed to pay more for it, or accept less for your money, as long as it’s “gaming.”

(A side note: by far the worst keyboards I have ever used were those made by the Apple company. In that Apple is famous for high quality products, I feel certain they will make a very good keyboard once they figure out what they’re for and why a person would want one.)

Only one of the keyboards I’ve mentioned is manufactured anymore, and even the survivor has an asterisk. There is a thriving secondary market for used ones and counterfeit new ones, but they’ve gotten pretty expensive. Newly manufactured keyboards today all are shot through with blinking LEDs and have volume controls and controllers for the blinking LEDs you’ve put in your computer, and such. Perhaps this is an indication that having followed “turbo” (and in the 1990s “digital”), “gamer” will be succeeded by “stoner.”

The asterisk: you can still get brand new Model Ms in a variety of configurations. They don’t bear the IBM name, but they’re the same thing, because they are made in the U.S.A. by the company that made many of the originals. In the 1970s, IBM farmed out its keyboards to a company called Unicomp, in Lexington, Kentucky. No one knows what if anything IBM now does for a living, but Unicomp still makes Model M keyboards. It is one of my favorite companies, in some measure because I’ve called them to say, “Okay, here’s what I want to do,” and they haven’t laughed at me. Well, a couple of times they laughed at me but did so in an amusing way. If you need some specialized keyboard thing, Unicomp is the first place to ask. They are big on custom keyboards. Within reason, they’ll build what you want. I don’t know if they still do, but they used to repair older Model M keyboards, too.

(Let me mention that no matter what keyboard you use, your life will be happier if you go to Walmart or someplace and get some of the non-slip shelf liner that looks like screen wire and a rubber mat had a baby. It can be cut to size and placed easily and it’s not at all sticky, but it keeps your keyboard firmly in place.)

I have one Unicomp device, which I’ve named the “Mighty Wurlitzer,” that has the most keys you’re likely to have ever seen on a keyboard. Many of the keys are programmable, though I’ve never programmed any. In fact I’ve used only the same keys I use on a normal keyboard. But it looks cool and menaces the unsuspecting. The musical reference isn’t entirely silly. A keyboard is to a writer as his instrument is to a musician.

My favorite of the Unicomp keyboards is the Mini M, a regular Model M without the number pad taking up four inches of space at the right end. What do you want? A place to put your coffee mug or arithmetic? There is one from the days of IBM livery, when it was called the Compact Model M, that is constantly by my side here at the desktop machine, as a silent you-can-be-replaced warning to the Storm, like Tony Hendra and his cricket bat in “Spinal Tap.” It is the only keyboard I do not hesitate in recommending, though the keypress is slightly firmer than that of the stylish “stoner” models. It is a serious keyboard for serious work. It can be relied upon.

Which is why I have a supply of them in both IBM and Unicomp livery, a lifetime’s worth. They’re stored upstairs, next to the strategic reserve of IBM Selectric typewriters.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Join the Conversation

Correction and amplification

I remembered the small Model M as having been called the “Compact,” but I was in error. It was the “Space Saver Keyboard,” or SSK. Not that it matters — I looked around online and used ones begin at about $500 and go up from there. They are great, but not $500 great, unless you got your first kiss while typing on one or something.

A far better deal is the Unicomp Mini M at $159, with an extortionate shipping charge. Or find a cheap “tenkeyless” keyboard that has a sound and feel you like, but be aware it won’t last as long and make sure you can turn off its flashing lights.